Stigma makes it harder for unhoused people to find stability, and the terminology used by CU Boulder students isn’t helping

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Colorado has faced a severe housing crisis due to failing structural systems, growing economic inequality and social stigmas

By Maryjane Glynn and Charlie Wallace

In Boulder, Steven Baribeau, known locally as “King Wook,” currently lives unsheltered under the Broadway underpass on the Hill. Baribeau, who introduced himself as Sheba, said the way that the City of Boulder deals with individuals experiencing homelessness “doesn’t let me participate in society.”

The term “wook” is a widely known phrase used by people who live in the Boulder area, including students who attend the University of Colorado. Wook is used to describe people who are experiencing homelessness.

While the Boulder community offers a variety of different programs to help people who are experiencing homelessness find housing and employment, unhoused people still face discrimination on a daily basis. Ultimately, using the term wook to describe someone who is chronically homeless, and who struggles financially, socially, politically and legally is dehumanizing and harmful for not only them but our society.

With that being said, Sheba has found his own nontraditional way of participating in society. He believes that he has put more work into the maintenance of the Broadway underpass than anyone else– including the city.

“I’ve been horrified that nobody cleans the inside of the tunnel,” Sheba said. “I’m the only one that’s ever cleaned graffiti, picked up feces, and washed vomit to get rid of it.”

Programs exist in Boulder that provide assistance to those experiencing all stages of homelessness, allowing them the opportunity to contribute to their community.

Molly East is the executive director of Focus Reentry, a nonprofit that supports citizens who have been previously incarcerated in the Boulder County Jail. Focus serves to promote second chances and reduce the likelihood of repeat offenses through assistance finding housing, counseling, jobs and peer mentoring.

According to data from the Prison Policy Initiative, formerly incarcerated people are 10 times more likely than the general public to face homelessness.

The purpose of East’s job is to help previously-incarcerated individuals reintegrate to society through case management. Through her work, she has noticed the unrealistic financial expectations people who are employed have for those experiencing homelessness.

“The way people are often treated with regards to technology or fees like an application fee, it’s like, oh my god, you know, $75 for an application fee, and this is somebody who barely has anything,” East said. “And so they’re shut out of those processes.”

As a case manager, East has witnessed how those experiencing homelessness are looked down upon by individuals with a permanent residence.

Referring to city employees, East said, “They’re more often talking to us about the person right in front of them rather than talking to them like a person.”

When working with those who are experiencing chronic homelessness, East’s responsibilities are to help her clients access everyday resources that they need in order to live. For example, she helps people get local bus passes, finds companies that would hire them and assists them with making doctor appointments.

From there, East assigns a volunteer mentor from the community to help people who are experiencing homelessness work through the tasks the case manager has set up.

“So, it’s somebody who walks alongside them,” East said. “This person goes with them and helps them navigate all those different things.”

In addition, she said she wants to see community members have more compassion for those experiencing homelessness.

“Nobody wakes up and says, I want to be homeless someday. And there’s almost always an underlying cause,” East said. “And it’s not laziness or drugs or all these stereotypical things that people put in their minds. It’s really somebody who has fallen in some pretty hard circumstances.”

People with steady housing often don’t understand the circumstances that push individuals to homelessness. This is a widespread problem in Boulder that advocates are working towards changing.

Vicki Ebner is a homeless policy manager who works with a variety of different organizations, case managers and local funding agencies around Boulder County to help find support for people who are experiencing chronic homelessness.

Ebner described a chronically homeless person as someone who has not had access to a consistent living environment for a long time. People who are chronically homeless are usually experiencing some type of “disabling condition” that makes it difficult for them to participate in societal activities such as finding employment and a place to live.

Ebner explained that those experiencing chronic homelessness typically qualify for permanent supportive housing (PSH), which is most often paid for by the federal government in combination with employment training and other social services.

The recipients of the PSH voucher can use it to rent a fixed nighttime residence as long as they adhere to the rules of the program. While the transition into a semi-permanent residence is a crucial step to the reintegration process, many challenges still remain.

“They have to relearn everything and it can be really isolating to be placed into an apartment, and it can be really challenging,” Ebner stated. “So what our responsibility is (as) a system is to make sure that they are getting the support they need.”

In Boulder, University Hill is a unique junction that showcases the diversity of campus life here at CU. The different lives of students, families and those experiencing homelessness intersect on “the Hill,” as it is most commonly known by Boulderites. While the Hill is a crucial hotspot for off-campus college life, it simultaneously highlights the key features of the homeless crisis in Boulder.

The frequent interactions students have with those experiencing homelessness has formed a culture where students refer to them as wooks, creating a caricature of the stereotypical homeless individual.

While the term wook is not officially defined anywhere, it is most widely understood in the way Urban Dictionary defines it: “Short for wookie. Plural: wooks. The dirty, vagranty variety of hippy. Almost always unemployed, following around jambands or festivals, and ripping people off. Known more for their tactics than their beliefs (unlike the more respectable hippy).”

Even without spending a lot of time on the Hill, the stigmas associated with homelessness in Boulder are plain to see. Mitchell Eby, a freshman at CU, described his perception of the term wook used locally to mean “a crazy tweaker homeless person.”

In Boulder, the term wook has become a big part of CU students’ vocabulary. However, the people being called wooks are highly vulnerable, and their lifestyle is not by choice, carefree or easy.

This terminology has been taken to the point where a man has been crowned “King Wook.” This man, Sheba, is popular among CU students who glamorize his lifestyle by publishing “wook” content on popular social media platforms like Yik Yak, Instagram and Snapchat.

Dylan Johnson, a first- year student at CU Boulder, picked up on how his peers interact and treat Sheba.

“[CU students] see him on the Hill and everyone’s like, KING WOOOOOK,” Johnson said.

Erin Olesiewicz, a fourth-year student at CU Boulder, brought attention to how the wook lifestyle is specifically for people who are experiencing homelessness on the Hill. CU students tend to act out more toward those living unsheltered on the Hill due to the normalization of the term wook and the nightlife scene.

“I feel like more people call them wooks around here than homeless people around Pearl Street, in a sense,” Olesiewicz said. “I think there’s more interaction with homeless people on the Hill. And it’s usually interaction when either they’re under the influence of something or we’re under the influence of something.”

Raichle Farrelly, a CU teaching associate professor as well as the TESOL Coordinator for the Department of Linguistics, explained how the widespread adoption of the term wook could normalize students’ lack of respect towards people experiencing homelessness and lead to dehumanizing these individuals.

Farrelly emphasized the power language can have in giving social meaning to words and questioned the use of the term wook due to the lack of consent given by the people to whom students reference with the word.

“The other thing about assigning social meaning to languages …[is do] they have any say in what that word means to them and about them? Has anyone asked them how they feel about being referred to in that way?” Farrelly asked.

During the interview process, these reporters asked Sheba if he likes being referred to as King Wook, and his response was straightforward.

“I’ll go with just the name that I’ve been using for like 40 years… It’s Sheba”.

Farrelly further explained how the students’ lack of empathy towards those who are chronically homeless can be damaging to our society.

“It puts a wedge between people’s relationality to one another, and it sort of obstructs empathy and compassion and understanding,” she said.

Regardless of where they live, people who experience homelessness face the same struggles, discrimination and lack of respect everywhere.

Sheba said he has recently been fighting a self-proclaimed “battle with the city.”

“They gave me camping tickets, and then they turned a camping ticket into a tent ticket as soon as they passed the tent law, even though the camping ticket had been issued at a date before the tent law was in place,” said Sheba. “They still tried to pass a law and then retroactively charge me with it.”

This ticket is formally referred to as the 5-6-10 Camping or Lodging on Property Without Consent. Citizens of Boulder are not allowed to camp outside any “park, parkway, recreation area, open space, or other city property” or “within any public property other than city property or any private property” without being granted permission from an officer who has oversight of that property or the “owner of private property,” according to the City of Boulder Colorado Municipal Code.

Boulder’s municipal code officially defines camping as to “reside or dwell temporarily in a place, with shelter, and conduct activities of daily living, such as eating or sleeping, in such place.” It is important to note that camping does not include napping in the daylight or picnicking.

This same code also defines shelter as “Without limitation, any cover or protection from the elements other than clothing.”

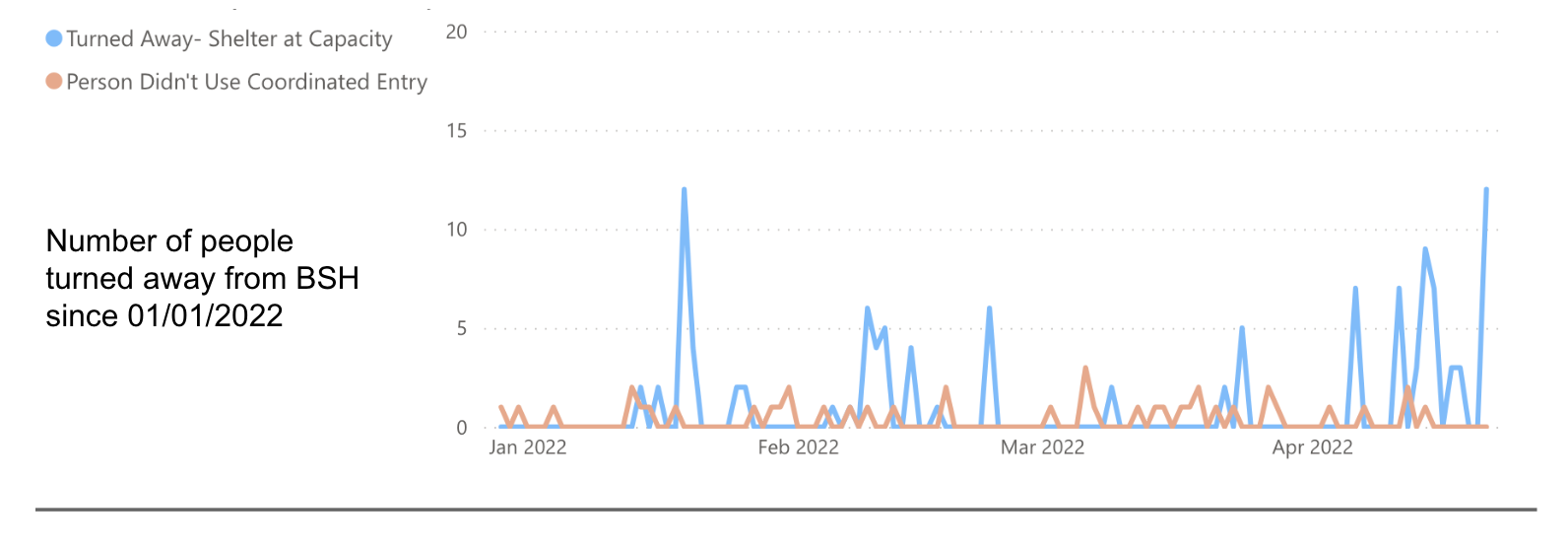

The Boulder Shelter for the Homeless, located on 4869 N. Broadway, offers a place for unhoused people to stay. It is open from 5 p.m. to 8 a.m. from Monday through Sunday. As of April 20, they provide 160 beds.

There were 97 turnaways due to capacity limitations this year, according to the city of Boulder’s shelter utilization dashboard’s most recent data.

In order to receive support from the Boulder Shelter, individuals must first go through the coordinated entry process. This year Forty-one individuals seeking supportive services have been turned away from the Boulder Shelter because they did not use the coordinated entry process.

Adults without children experiencing homelessness in Boulder can access supportive services through the coordinated entry process Monday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., and Tuesday from 12 a.m. to 4. p.m., by either calling 303-579-4404 or walking up in-person to the Age Well Center at 909 Arapahoe Ave.

Through the coordinated entry process, a staff person will determine the services needed to be provided to the individual. Coordinated entry helps pair those experiencing homelessness with crucial services such as shelter, basic-needs services, case management, and more.

Those individuals experiencing homelessness in Longmont can access coordinated entry Monday to Friday from 12 p.m. to 7 p.m. by calling 720-453-6096 and walking in at HOPE on 804 South Lincoln St. on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday or Friday from 12 p.m. to 5 p.m. On Wednesday, in-person coordinated entry can be accessed at 1335 Francis St. from 12 p.m. to 5 p.m.

If an individual needs help outside of these hours, they can go to the Boulder Shelter, from 5 p.m to 7 p.m. and complete the process at the next available time.

Sheba’s experience with being chronically homeless exemplifies the struggles, stereotypes, lack of respect, human decency and rights given to people who are experiencing homelessness.

While living on the Hill, Sheba has struggled with receiving camping tickets, dealing with intoxicated individuals, and both physical and mental abuse from people he interacts with on the hill, whether they are CU students or others in the community.

With that in mind, Sheba said that his temporary accommodations this year were more comfortable compared to other years. In previous years, Sheba lived on state highway property, right beside campus under a tree, but he stated that he had to move from this location to the underpass on the Hill.

According to a school official, Sheba said, “there’s some campus property between me and the embankment on the other side of that state highway property,” he said. “The path is the county and city and parks’ multi-use pathway. Campus doesn’t begin until the red concrete.”

Sheba uses recyclable materials around the hill in order to keep himself safe, dry and warm throughout Boulder’s unpredictable weather.

“It was actually extra cozy—this past winter was the first winter I’ve been dry and not terribly cold,” Sheba said. “I had made myself a platform of plywood and four by fours and had a lot of, you know, your body length mirrors, cute cardboard boxes that come in and then styrofoam.”

Sheba believes that he contributes to the city through voicing his opinions persistently and to the right people.

“I think my lip and mouthiness and really being insistent and demanding that city authorities take health and safety issues that I bring forth to actual relevant conclusions so that something is done about them,” said Sheba.