30 years onward: Colorado, once the “Hate State,” now a leader in LGBTQ+ rights

By Cayden Stice

Colorado and the LGBTQ+ community have held a fraught relationship, with no moment more contentious than the 1992 passage of Amendment 2. In the thirty years since, the state has progressed on queer civil rights, and become a national lodestar in LGBTQ+ equality.

Note: throughout this article, the abbreviation of “LGB” is used to reflect the historical context of queer politics.

A year of tension

Colorado was the “Hate State”—or so said the national boycott in 1992.

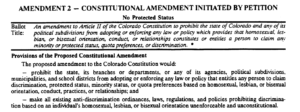

In November of that year, voters took to their ballots with a majority approving Amendment 2, an alteration to Colorado’s Constitution that forbade the state and its local governments from recognizing sexual orientation as a protectable status. This change resulted in the prohibition of all anti-discrimination laws protecting LGB people.

The Amendment 2 push was the product of Colorado for Family Values (CFV), a conservative Christian social group headquartered in Colorado Springs. In contrast to more left-wing cities in the state, Colorado Springs was and remains a conservative stronghold.

CFV emerged as a counterpunch to progress made by pro-LGB civil rights groups in Colorado. Throughout the 1980s and into the early 1990s, grassroots activists had campaigned for LGB anti-discrimination measures in multiple municipalities, including Denver and Boulder. CFV aimed to curtail those expansions and push a conservative vision of morality and politics.

On the campus of CU Boulder, the Amendment 2 campaign took center stage for the school’s football team, where head coach Bill McCartney brought his political and religious views to the field.

He denounced homosexuality as a “sin” and an “abomination,” leading to his support of Amendment 2.

McCartney faced both support and opposition for his stances on campus. As a decorated football coach, he guided the CU Buffs team to a national championship and multiple bowl title wins. The upward trajectory for the team led many supporters to rally around the coach.

Pro-LGB activists alleged that regardless of McCartney’s dominance on the field, his messaging was divisive, dehumanizing, and detracted from CU’s values.

“We are all made in the image of God,” wrote one demonstrator to a local newspaper.

McCartney responded to dissidents by saying, “As a man who feels strongly about certain values, I do get involved and will continue to get involved in these issues… [Amendment 2 is] not trying to take away anyone’s rights. But they are saying that a lifestyle doesn’t entitle you to special rights, and I agree with that … [Homosexuals are] a group of people that do not reproduce, and yet they want to be compared with groups of people who do reproduce.”

As a university, CU did not take a stand against McCartney’s divisive messages. Then-President Judith Albino stated, “Like any member of the university community, coach McCartney has the right to express his personal views and participate in organizations of his choosing.”

With the campaign for Amendment 2 unfolding, tension continued to build. Materials produced by CFV perpetuated lies about LGBTQ+ people, including accusations of grooming and sexualization of children. Further materials from CFV stated that queer people were asking for “special rights” in anti-discrimination laws, falsely insinuating that protective legislation took away from heterosexual abilities.

Polls before election night indicated narrow margins. On election night, Nov. 3, 1992, 53.4% of voters approved Amendment 2, overturning years of LGB activism and thwarting future abilities at expanding anti-discrimination measures.

75% of Boulder voters rejected the anti-queer legislation, while Denver voters rejected it by a narrower margin. Colorado Springs voters strongly favored the legislation, helping push the final tally to passage.

“It is not you who are gay and lesbian who have lost tonight—it’s all of Colorado who has lost tonight,” stated then-Governor Roy Romer in a speech after the results were tallied.

Amendment 2’s passage did not happen in a vacuum. Throughout the early 1990s, multiple states had similar attempts to pass anti-LGB legislation. In Oregon, voters on the Nov. 1992 ballot were asked if the state should “discourage homosexuality, other listed behaviors, and not facilitate or recognize them.” In 1994, Idaho voters were asked if there should be a bar on LGB-specific protection in the state’s anti-discrimination laws.

But unlike Oregon or Idaho, Colorado’s initiative passed, and with it came a collective grief among the state’s LGBTQ+ residents. For some queer people in the state, the passage of Amendment 2 instilled a depression. After years of legal equality in cities like Denver and Boulder, Amendment 2 symbolized a reversal of the progress that had been made.

As media attention around the amendment’s passage grew, so did the uproar from coast to coast. Conventions and movie studios yanked their projects from the state, and prospective tourists were encouraged to steer out of the Centennial State.

A New York Times article from Dec. 1992 remarked, “[Colorado] has always enjoyed its image as a beautiful land where tolerant, progressive people live in a casual atmosphere. It has always been considered rather hip to be a Coloradoan. Now suddenly the anti-gay-rights vote has cast an entirely different image: a backward state that wishes to discriminate.”

The slogan “Hate State” became synonymous with the politically-rocky state. National boycotts encouraged tourists and movie productions to find other states as Hollywood and celebrities began advocating a reversal of Amendment 2.

In cities like Boulder, queer people continued finding ways to converse and organize. At the Walnut Cafe, activists found community and new strategies for charging ahead. While momentarily defeated, the movement for LGB rights persisted.

With state law hampering forbidding anti-discrimination legislation on the basis of sexual orientation, LGB activists turned to the courts for effective change. Jean Dubofsky, a Boulder resident and the first woman on Colorado’s Supreme Court, became a source of hope for moving forward. A lawyer by trade, Dubofksy led a multi-year litigation effort that landed in front of the Supreme Court.

After multiple years of litigation, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Amendment 2 in the 1996 court case, Romer v. Evans. The court found the amendment in violation of the Equal Protection Clause in the 14th Amendment, as it singled out a particular group of people and denied their ability to seek legal protection.

“If the constitutional conception of ‘equal protection of the laws’ means anything, it must at the very least mean that a bare desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot constitute a legitimate governmental interest,” wrote Justice Anthony Kennedy.

Progress made, progress ahead

In 2022, the same debates about the civil rights and representation of LGBTQ+ people remain throughout the United States.

Earlier this year, Florida political leaders rallied for the infamous “Don’t Say Gay” Bill, limiting discussions of queer topics in elementary schools. In Texas, politicians have sought to limit gender-affirming care for transgender youth, a practice being replicated in other states.

Colorado, though, has largely resisted this conservative pendulum swing.

Since 2018, Democrats have held a government trifecta, holding the state House, state Senate and the governorship. The state has not elected a Republican governor since 2002, though each chamber of the state legislature has traded political party power over the past three decades.

Only one Republican remains elected statewide: Heidi Ganahl, who presently sits on the University of Colorado Board of Regents. Ganahl is currently running in the 2022 Republican gubernatorial primary.

With this political shift has also come more favorable policies for queer people. Since 1992, Colorado has amended its hate crimes protections to include queer people and has extended same-sex adoption laws. In 2014, the state legalized same-sex marriage, a year before the nationwide Obergefell v. Hodges case.

In 2021, Colorado was named as one of the United States’ leading states in LGBTQ+ equality. Where other states are now advocating for the removal of LGBTQ+ content in schools, Colorado requires LGBTQ+ representation in curriculum—though, how that looks remains contentious.

Similarly, where other states restrict the ability for gender-affirming legal recognition, Colorado’s has expanded access for transgender and non-binary people to update their identity documents. Jude’s Law, passed in 2019, allows changes to gender identification on birth certificates and driver’s licenses, without the need for surgical intervention. The law also removes the requirement for name changes to be published publicly.

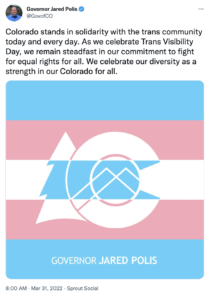

In 2018, the state also made history in electing Jared Polis, the nation’s first openly-gay elected governor.

Brianna Titone, a current state Representative and chair of the legislature’s LGBTQ Caucus, met with The Bold to reflect on Colorado’s journey from Amendment 2 through the present day. Titone, the first openly-transgender state legislator in Colorado—and the fourth in the United States—was elected in 2018.

“Since 1992, which was really our low point, we’ve come a long way in leadership, representation, and showing that we are willing to work harder to fight not just for our rights, but for everyone’s,” she stated.

Titone discussed the proactive work of the state’s legislature and governor.

“One of the objectives we’ve been trying to do is make sure we put protections in place now, to make it more difficult for bad policies to go in … I think that we really need to make sure that everybody who is supportive of the [LGBTQ+] community really gets out and starts to pay attention to what’s going on around the country,” said Titone.

She continued, “Because those kinds of things, just because we have not seen them here recently, because we’ve been able to hold them off, doesn’t mean they couldn’t easily crop up. And we can’t let our guard down … We have to maintain what we have right now.”

While the trajectory of LGBTQ+ rights in Colorado has not always been consistently uphill, laws and social attitudes have become more favorable since 1992. While acceptance and inclusion is not innate, queer Coloradans have continually advocated for and found success in extending their civil rights. Alongside allies, queer people have stayed resilient and unrelenting.