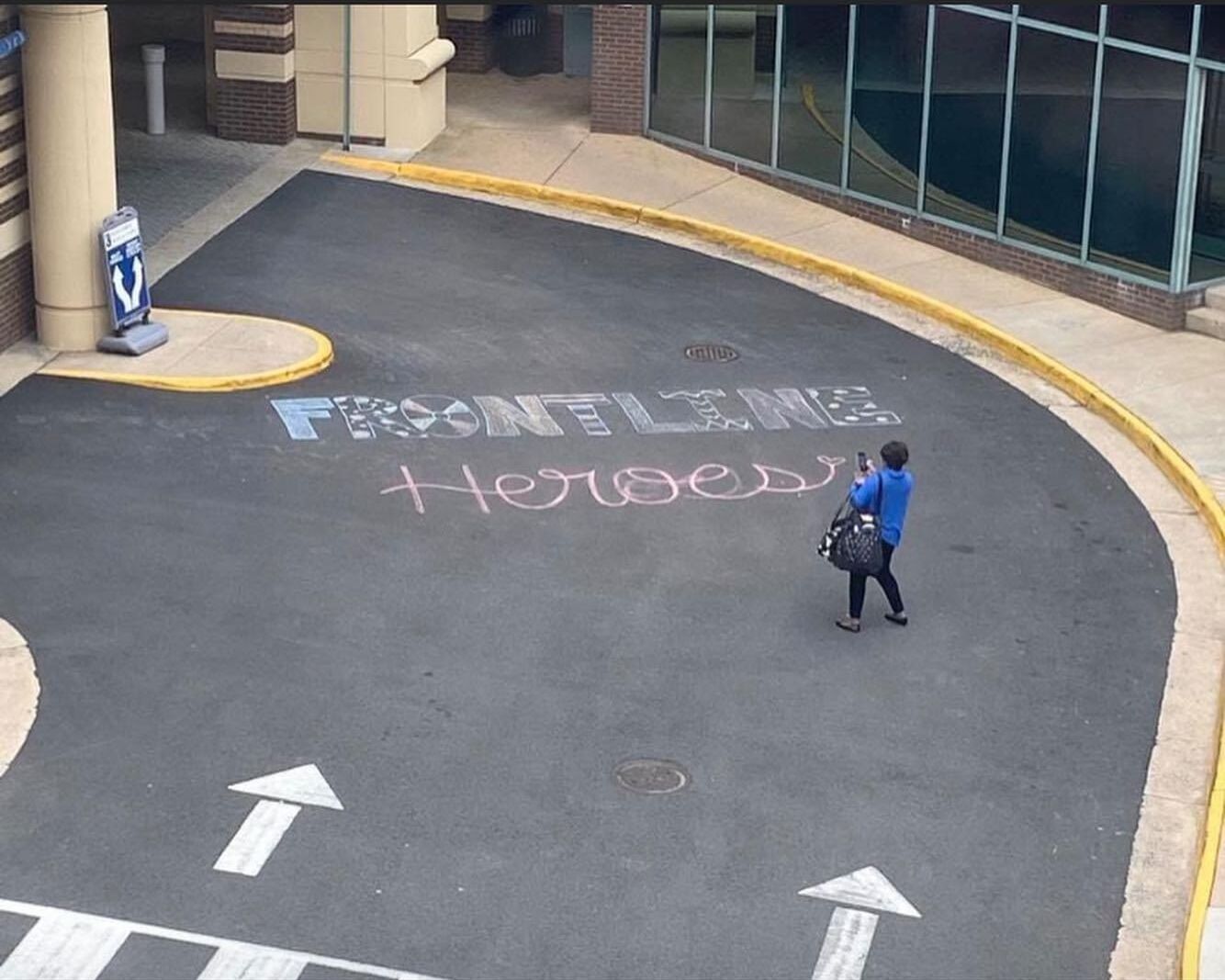

Frontline Heroes

A day in the life of medical professionals on the frontlines fighting the coronavirus.

By Joy Weinberg, Contributing Writer

This article was originally written for JRNL 4002: Reporting 2, documenting the experiences of doctors in the Chicago metropolitan area from March to June 2020.

Author’s Note: It’s March 25, 2020 and I’m on my way back home to Chicago. Coronavirus has struck the United States, and everyone is in full lock-down mode. As my boyfriend and I drive from Boulder, CO through the plains of Nebraska and Missouri, up to Illinois, we notice that the roads seem more desolate than ever. After 15 hours in the car, we finally make it back to our respective hometowns. The next morning, I am not feeling well and have body aches. In the days following, I experience vomiting and dry-coughing and decide that I must be tested for COVID-19. Sure enough, two days after the test, the phone rings and a doctor tells me that I have tested positive for the virus.

With college courses still being held online, I push through my illness to finish the semester. It’s a challenging task, to say the least. Since both of my parents are health care providers and more at risk for being seriously affected by COVID-19 due to their ages, I fully isolate myself in my room for the next 14 days. For my final reporting project of the semester, I decide to interview some of my dad’s colleagues who treat patients with COVID-19. I interview doctors and nurses via phone to get their perspective of what it is like to be on the frontlines battling COVID-19. These are their stories.

* * *

Woken up by the soft cries of her 2-year-old son, Gretchen Fox,wakes up at 4:30 a.m. and begins her morning routine. She gently picks him up and holds him close as she walks into the kitchen for her morning cup of coffee. Soon her other two kids, 4- and 5- years-olds, groggily walk downstairs to give their mom good-morning kisses. By 6 a.m. after many rounds of hugs and kisses with the little ones, Fox rushes out the door and drives off to work an unpredictable 8-hour shift.

This might seem typical of how any mother working a full-time job starts her day, but it is especially difficult for Fox, 39, who is an anesthesiologist working at the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center in Chicago on the front lines combating COVID-19.

Fox is among the many health care providers throughout the country who are helping COVID-19 patients daily. While many people are working from home during this pandemic, doctors and nurses continue to serve on the frontlines, risking their lives and the lives of their loved ones in an attempt to save those who have fallen ill to the deadly COVID-19 virus.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, 82,586 health care providers have tested positive for COVID-19 — as of June 20, the latest CDC figure. Of those confirmed, 457 health care providers have died in the U.S. as a result of COVID-19. The number of total confirmed cases and deaths from coronavirus continues to rise every day.

* * *

Dr.Fox pictured right

Fox’s mask helps protect anesthesiologists from becoming contaminated with COVID-19 as they provide medical care to infected patients.

Dr.Fox’s kids pictured below

Gretchen Fox’s kids stay busy bouncing on their in-home trampoline while their mother is busy at the hospital, helping COVID-19 patients.

Dr.Fox’s kids pictured left

Fox’s children play with each other, waiting for their mother to return after a long day of work!

Anesthesiologists are among some of the most at-risk health care providers during this time because their job requires they get extremely close to the source of the virus — a patient’s mouth.

“Our job is securing the airway,” said Fox’s colleague Janet Newman, who has been practicing anesthesia in Chicago for 28 years.

To secure a patient’s airway, anesthesiologists methodically place a breathing tube into a patient’s trachea, which is then hooked up to a ventilator that helps the patient breath.

“We have to get very close to the patient’s mouth, which then exposes us to all of the secretions of the coronavirus,” said Newman. “I’m definitely more anxious or nervous knowing what I have to do than if it were a routine intubation.”

Back on the road, Fox nears the end of her 3 mile commute to the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center, where she has been practicing for seven years. She walks through the hospital doors, takes a few deep breaths and steadies herself to face whatever the day will bring.

Around 2 p.m., towards the end of her shift, Fox receives a message on her pager that a COVID-19 patient needs to be intubated. She grabs a few bags filled with personal protective equipment (PPE) and hurries to the intensive care unit to help the struggling patient. She and Newman will work on this COVID-19 patient together. Today, Newman is working alongside Fox as her “buddy,” standing by in case Fox needs any help.

Before going in, the anesthesiologists must gear up—which means they cover up every millimeter of their skin with PPE. Fox and Newman each put on an N-95 mask and then another surgical mask over that. They each wrap a towel around their neck, slip on two pairs of surgical gloves, step into a full protective gown and put on a helmet with a full-face shield. This takes about 10 minutes.

Many health care providers have never had to worry about PPE to this degree. However, the high contamination risks of COVID-19 have made PPE a necessity that health care providers have had to adjust to.

“Everybody’s been kind of flying by the seat of their pants,” said Newman.

Suited up and ready to go, Fox heads into the ICU room to secure the patient’s airway. Newman, as Fox’s “buddy”, waits in the room right outside just in case Fox signals her for help. In the room with Fox is a nurse and a respiratory therapist. Together they work cohesively to get the patient intubated and make sure their vitals are stable.

Once done, Fox then leaves the ICU room to remove all of her gear. Taking off the PPE is much more dangerous and time-consuming than putting it on. This process, called “doffing,” creates an extra layer of risk for physicians to become contaminated because their protective gear has been exposed to the COVID patient

It’s 4 p.m. when Fox, exhausted, clocks out after a long day and races home to get back to her family. Since she intubated a COVID-19 patient today, Fox must strip down, throw her clothes in the laundry, and jump into the shower before interacting with her kids.

“It’s hard because we can’t really quarantine from our kids because they’re so little,” said Fox.

After watching the three kids all day, it is now her husband’s turn to go in for a late-night shift. He, too, will intubate COVID-19 patients.

Before bed, Fox will make a quick dinner for herself and her kids, help her 5-year-old with his remote kindergarten classwork, and put all of the kids to bed — all the while praying she did not bring COVID-19 home with her.

“There’s really no down time or any time to rest. That’s the hard part,” said Fox.

While the medical work for Fox is usually over by 5 p.m., for others, it is just starting. At the University of Illinois Hospital in Chicago, 5 p.m. marks the beginning of a 14-hour shift for anesthesiologist Cory Deburghgraeve, who has been practicing for six years. Typically, he works the day shifts in obstetrics helping pregnant women, but since the coronavirus hit, the new staffing model has him working exclusively in the ICU with COVID-19 patients. This model ensures that those who are willing to work with COVID-19 patients’ do not also work with patients in other units.

Deburghgraeve willingly offered to cover all of the weekday overnight shifts, where the hospital told him they needed the most help.

“I’m young; I’m healthy; I don’t have kids; I don’t live with older people, so I’m flexible, and I want to help,” said Deburghgraeve.

For Deburghgraeve, who is now working roughly 70 hours per week, one of the hardest parts of working through this pandemic is the emotional toll.

COVID-19 has caused unique circumstances in hospital visiting policies, restricting family members and loved ones from being able to visit patients in the ICU. For many COVID-19 patients who are at the point where they need intubation, the prognosis is grim.

“I’m potentially the last person they’re ever going to talk to. The last face they’re ever going to see,” said Deburghgraeve.

While most of the COVID-19 patients Deburghgraeve treats are in bad condition and unable to communicate, some patients are well enough that he is able to talk with them before they are intubated.

“I have had about 25% of patients who are very much awake and alert and who I can talk to,” said Deburghgraeve, “[…] and those conversations will be with me for the rest of my life.”

After intubating a COVID-19 patient, and if it’s not too busy, Deburghgraeve can go into a “call room” to try and catch some sleep; an hour or two would be extremely lucky. However, the emotional toll of intubating very sick patients and the anticipation of receiving another alarming call to action does not typically equate to getting a well-rested nap. His day ends at around 7:30 a.m., just as the rest of Chicago rises to take on another day.

For many medical practitioners, it’s hard to find the time, or mental capacity, to decompress. Even once they make it home, like the rest of the country, they too must shelter in place and remain isolated.

“I love spin class,” said Deburghgraeve. “It’s always been what I do to decompress after work or when I need some time to just focus on myself. And now that I don’t have that opportunity, I feel like I’m going a little stir crazy in my house.”

After getting some rest in the comfort of his own home, Deburghgraeves’ alarm rings around 3:30 p.m. It’s time to wake up and make his way back to the hospital for another grueling 14-hour shift.

“I feel like I’m in this constant cycle of sleep and then work, sleep, work, sleep, work, and there’s not really much time for myself,” said Deburghgraeve.

He repeats this schedule day after day, without question, and with a sense of purpose.

“I’m not doing this for myself,” said Deburghgraeve. “I’m doing it for other people. I know there’s risk involved in what we do and I’m willing to accept that.”

* * *

Nurses, who spend far more hours in direct contact with COVID-19 patients than do most physicians, put themselves at an even higher risk of infection.

“Guess what? It’s not the doctor standing between death and you — it’s me,” said Catherine Dembrow, an ICU nurse working at Inova Hospital in Fairfax, Virginia.

It’s 4 p.m. and Dembrow’s patient has had unstable vitals for almost an hour now. She refuses to leave the room until she feels confident that her patient’s vitals are stable. As she works to maintain the patient’s oxygen levels, sweat begins to drip down her back. After working to stabilize the patient’s vitals for over an hour, their oxygen levels are finally stable enough to where Dembrow can step out of the room for a breather, even if just for a few minutes.

“I sweat so much that the little foam piece on the bridge of the nose on my mask was like a sponge,” said Dembrow.

After trading in her sweat-filled mask for a new one, she goes to a room nearby to check on another COVID-19 patient. Although the patient is intubated and not awake, Dembrow climbs behind the hospital bed to brush and braid this patient’s badly matted hair.

“I only did that because it’s something I would want someone to do for me,” said Dembrow.

Working around the clock in emotionally taxing situations, doctors and nurses give their all to every single patient that is rolled through their hospital doors.

Amidst all of the intensive work these health care providers are doing, many do not consider themselves heroes — for them it’s just part of the job.

“I can’t imagine a world where I would not be doing this,” said Deburghgraeve.