Joy Is an Act of Revolution

Historically, joy as an activistic tool has been underscored by more mainstream forms of protest like pride, anger, and outrage. However, in her new book, Kristie Soares, assistant professor of women and gender studies and co-director of the LGBTQ studies certificate program at the University of Colorado, talks about the importance of joy in Latinx media and its importance in political work.

“To take joy seriously as a political tool and to take seriously the people that enact it,” remarked Soares. “But beyond that, I think to take seriously affects, feelings, and emotions.”

Kristie Soares started her research as a way to explore how joy is employed in media produced by the Puerto Rican and Cuban diaspora – the small groups of people living away from their homelands – to change dominant narratives about gender, sexuality, race, and class.

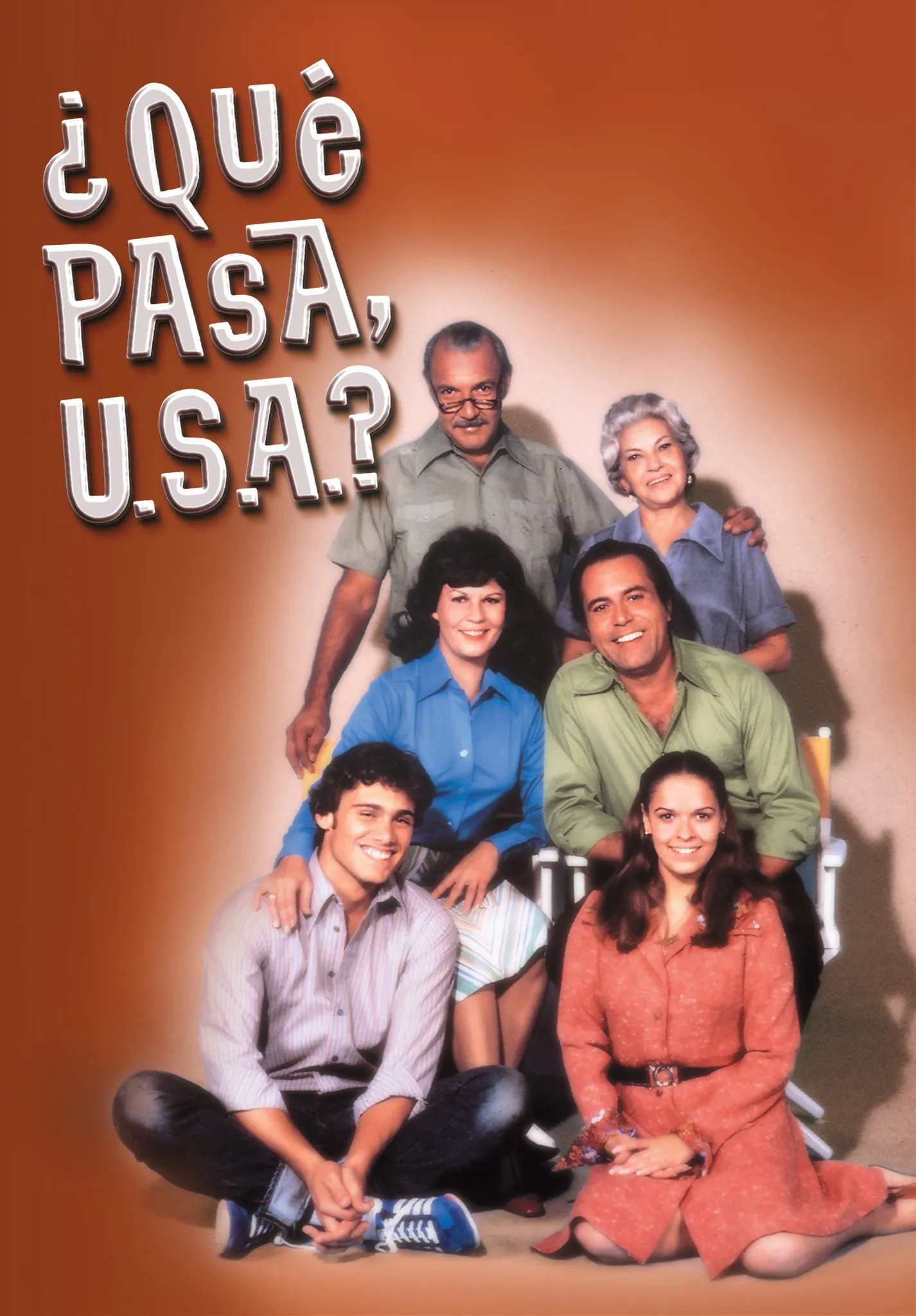

She takes a look at the salsas from the late 1960s to the early 1970s, to the New Young Lords Party, to the first bilingual sitcom produced in the U.S., the aptly titled Que Pasa U.S.A?.

Soares also takes a look at the songs of Celia Cruz intertwined with the Pulse Nightclub massacre in 2016 and the discography of Pitbull.

These productions explore five types of joy that Soares describes in her book as: gozando (enjoying oneself or taking pleasure in),, choteo (“kidding” or “playing around with,”) azucar (literally sugar, an iconic catchphrase by Celia Cruz) and dale (loosely going for it, Pitbull’s characteristic phrase) and the more abstract precise joy. They each explain a particular side of joy as an activistic tool for Puerto Rican and Cuban media producers.

Both Puerto Rico and Cuba have a violent history with the United States. Puerto Rico is still an American colony and while Puerto Ricans are American citizens, they don’t have federal voting rights while they live on the islands.

On the other hand, Cuba’s revolution worsened the strain between relationships with the U.S. It was the start of Cuba as a socialist country that allied itself with the Soviet Union. It led to a great migration into the U.S. of Cuban exiles, a term used to refer to many of the older Cuban residents who fled Cuba in protest during the revolution.

However, many of the recent migrants have come looking for better economic opportunities.

These migrations have led to large, vibrant Cuban and Puerto Rican communities in the U.S., especially in places like Miami and New York City. So, why research the use of joy as an activistic tool in such a violent and controversial history?

“We think of emotions as the opposite of how you need to ground yourself to be political. This old idea that women are too emotional for politics, right? We see the same thing with people of color and other groups,” Soares explained. “But this can be precisely an activist’s greatest strength, to ground their politics in their lived experiences and emotions.”

What Soares found in her work was a surprising range of media produced towards empowerment, with joy as the focal point. One of the songs she analyzes in her book is “Anacaona” by Fanial All-Stars.

This song’s lyrics tell a story of colonization through the life story of a woman of indigenous descent whose freedom never arrived, and she belonged to a captive race. Now, a song such as this could have been taken as Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit, but instead, this is a party song with upbeat tones that people dance to —it is a social critique masked with pleasure.

“I’m Mexican and it bothers me a lot, some of the stereotypes I see in the media,” Juliana Prat, a second-year student at the University of Colorado Boulder commented. “Like the assumptions of immigrants stealing jobs or this whole tacky animal print clothes representation of how we dress. We are more than that.”

From Sofia Vergara’s portrayal of Gloria Pritchett with over-the-top animal print outfits in the show Modern Family to Rita Moreno’s Lidya with her over-the-top dresses in One Day at a Time, Latina women in media are usually mocked for their “exuberant and sexualized attires,” and presented as “overproduced women,” who are loud and hot-headed while men are portrayed as sketchy, low-income, and criminal, as seen with George Lopez’s Rudy Reyes in Blue Beetle.

These are the dominant narratives Soares’ pieces of analyzed media seek to change, while highlighting the instances Latinx media has been used as political tools to advance their communities instead of continuing a spiral of oppression.

When exploring choteo, “kidding” or “playing around with,” she looks at an episode from the first bilingual sitcom in the country, Que Pasa U.S.A?, a story about a Cuban exile family living in Miami. During this episode, the heterosexual cisgender son of the family has to work on a class project about gay people.

In reaction to this, the family starts worrying the son himself is gay, and their exaggerated reactions poke fun at discriminative views and misunderstandings of the LGBTQ community. The choteo is used to leave the audience with a message of comfort and acceptance of what a gay person is.

There are other three types of joy that Soares explores in Playful Protest, but perhaps the most impactful of her research is Celia Cruz’s songs intertwined with the Pulse Nightclub massacre in 2016, also known as the Orlando shooting of 2016.

According to Britannica, up to that year, it was considered the deadliest shooting in the country, with over 50 people injured and 49 deaths. The nightclub was famous for being a hot spot for the LGBTQ community, but the shooting also happened during Latinx night – targeting both communities in a deadly event.

It was while exploring the aftermath of this shooting that Soares found Puerto Rican transgender and queer people using Celia Cruz’s songs to mourn the shooting. They were dancing in the sites of the vigils as ways to reclaim joy in the midst of mass homophobic violence.

“You wanna see joy in Latin culture? You don’t have to look far away. Look at the dining hall workers. Many of them are Hispanic and working with kids who will barely even look at them, and it is very sad,” Prat asserted. “And yet, they are always so happy. You give them nothing and they are still happy. It is a part of us. It is our resilience.”

CU Boulder is not usually seen as a diverse environment, where these stories might not seem important or local enough. But, Soares’ book Playful Protest brings a tiny piece of what Boulder people can offer and what they still need to be exposed to. In Prat’s words, the experience might be right in front of them.