Recognizing Indigenous Peoples Day: Boulder and the Sand Creek Massacre

Boulder County recognizes Indigenous Peoples Day with a conversation table hosted by Right Relationship Boulder and local Cheyenne-Arapaho leaders

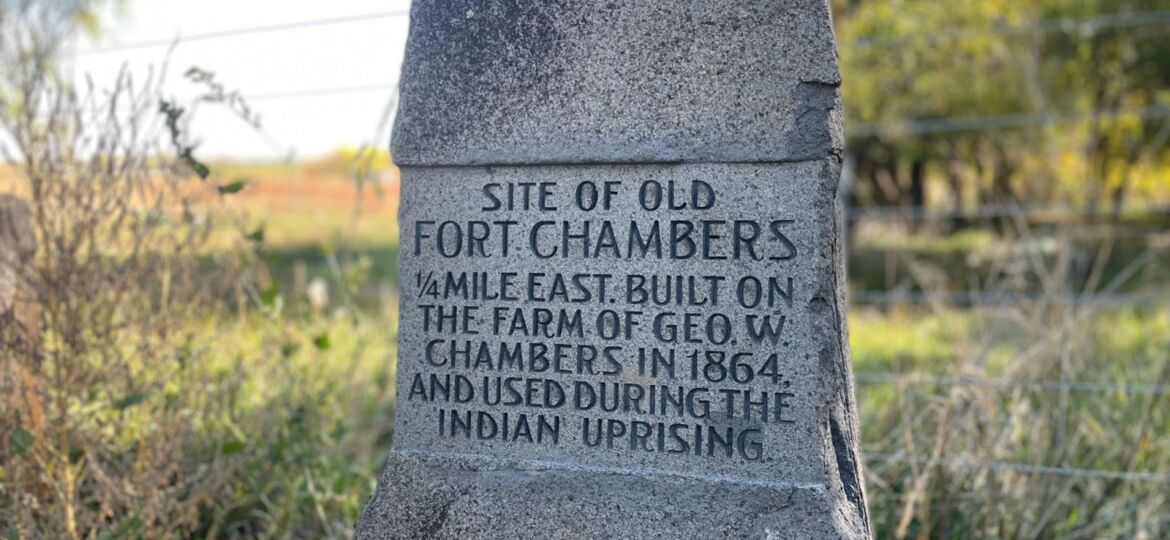

Site marker of Old Fort Chambers located at Boulder’s Fort Chambers site

On Monday, Right Relationship Boulder hosted a slide presentation by CU research professor, Christine Yoshinaga-Itano, CU graduate student, Saydie Sago and Right Relationship Boulder director, Paula Palmer as a part of Boulder’s 2022 Indigenous Peoples Day celebration events. The Native American advocacy organization focuses on building community, uplifting voices, educating people on unwritten histories, healing from generational traumas, and creating the “right relationship” between Boulder and its Native communities.

The presentation, titled “Current Conversations, Fort Chambers: Boulder’s Role in the Sand Creek Massacre,” informed attendees about the details of the Sand Creek Massacre and the history of Boulder’s Fort Chambers site.

“Fort Chambers was built on a lie,” said Southern Arapaho leader Fred Mosqueda when asked about the Fort Chambers site. The stone site marker depicts a story far different than the Cheyenne-Arapaho know.

The Sand Creek massacre took place in 1864 after the Cheyenne and Arapaho Native American tribes had been pushed west to what is now the Denver Metro and Boulder Valley area. The Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes had been known to be peaceful—however, the American colonial soldiers (many of whom were prominent Boulder residents at the time) went to the Cheyenne and Arapaho village and killed 230 of the Native civilians. Most of the victims were women, children and elders. The returning soldiers were greeted with noble honors.

The presentation also highlighted the role of the Fort Chambers and Poor Farm space in the Sand Creek Massacre. Its historic use as a planning ground for the massacre serves as a reminder of the injustice to the Cheyenne-Arapaho in Boulder.

Boulder County owns 110 acres of the Fort Chambers space, and Right Relationship Boulder is strongly encouraging the county to use it for restorative justice purposes for the Cheyenne-Arapaho tribes.

“Right Relationship Boulder is urging the city to recognize the uniqueness of this land… we are asking the city to follow the direction of Indigenous leaders,” said Palmer.

The event also included a short conversation with Mosqueda as well as Cheyenne leader Chester Whiteman.

“I would appreciate it if the City of Boulder would collaborate with the Cheyenne-Arapaho on something that would help us get back into Colorado so we could tell our story,” Whiteman said.

He further elaborated that reparations for the Fort Chambers could include education, Native cultural embassies, land harmonization and increased collaboration with Boulder and Colorado leadership.

However, working on the site hasn’t come without difficulties, as the Cheyenne-Arapaho acknowledge the legal hurdles of gaining this land back.

“The governors and legislators would have to be included in this because we can not do anything individually—they would need to become involved,” said Mosqueda.

Supplementary plans for restorative justice have also included collaboration with the Boulder Valley School District (BVSD) to teach more Indigenous peoples’ history.

Right Relationship Boulder has been aiding this goal by providing resources to BVSD on Indigenous voices, cultural events, and the side of history that has not been historically taught in many American school systems.

The organization has also been providing students with language camps and more access to Cheyenne-Arapaho history in Colorado through its visiting group.

“You can’t live a culture without the language. So we need to continue always teaching that,” Whiteman said.

Right Relationship Boulder and Indigenous leaders have plans to continue and accelerate their collaboration with Boulder County.

Colorado is one of ten states to celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day in place of Columbus Day. Boulder, however, has been unique in its approach to reparations for the Cheyenne-Arapaho because of its county-to-tribe negotiations.

The Boulder Valley hopes to become a model for other regions nationwide when it comes to working with Native communities toward restorative justice.

“It is time for us to become established as the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes of Colorado,” Mosqueda said.