Illicit fentanyl’s role in CU Boulder culture has poisoned community members

On National Fentanyl Awareness Day, this story is being cross published in The Bold and the CU Independent. Both publications believe in its importance to the university community.

Shubhashika Singh, The Bold CU Editor-in-chief

Henry Larson, CU Independent Editor-in-chief

Text by Hannah Prince

Photos by Alec Levy-O’Brien

Tami Gottsegen doesn’t come to Boulder anymore. The 45-minute, northwest drive from Centennial is too painful: it is where her son, Braden Burks, 24, attended the University of Colorado. It was a place of hope and promise for Tami until her son’s life was taken from him by a counterfeit pill.

Braden was a true Colorado native: a strongly devoted Broncos fan, glued to his television on Sundays, an avid skier, namely at Breckenridge, Keystone and Winter Park, and in-state college student who studied at Leeds School of Business.

“Living in Winter Park as a child, he learned how to ski when he was still in diapers,” Gottsegen said. “As soon as he could walk, he was skiing.”

He grew up in a tight-knit, blended family and was one of six siblings. His stepsister, Tori Bridges, describes her bond with Braden as twin-like. Bridges describes her brother as popular and well-respected by peers, a magnetic personality that acted as a glue in his many friendships.

When Braden moved to Denver in 2017, he was beginning a new chapter in his life.

On Jan. 10, 2019, Braden had two friends over to watch a NCAA men’s basketball game. Watching sports and participating in them connected Braden and his friends in shared interests and passions. But after Braden’s friends left, his night was different than most – he decided to buy a pill from a high school acquaintance.

Throughout his life, Braden struggled with chronic sleep issues, even trying weighted blankets, melatonin and other options to improve sleep quality but could not find restitute. Gottsegen said she believes the reason he bought the pill was to get sleep, but what Braden thought was oxycodone was disguised. It was a counterfeit pill, containing illicit fentanyl.

Braden’s brother found him unconscious the following afternoon at his condo, after Gottsegen worried about not being able to get ahold of him. By the time EMTs arrived, too much time had passed for the medics to revive Braden with the only drug able to reverse opioid overdose, Narcan.

Fentanyl is a Schedule II narcotic, a synthetic opioid first used medically in the 1960s, typically used to treat patients with severe pain, particularly cancer patients.

It is also used to treat patients with chronic pain who are not physically tolerant to other opioids because it is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. In recent years, it has become a dominant painkiller for doctors, but also a scourge in communities as black-market cooks realize easy profits can be made because a small amount goes a long way.

Fentanyl is now disguised in street substances, such as powders, capsules and pressed pills. It is Colorado’s leading cause of drug deaths.

According to Kirk Bol, the manager of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment’s Vital Statistics Program, at least 912 drug deaths in Colorado in 2021 involved fentanyl. Drug poisonings by fentanyl have increased over 2,000% since 2015, when only 41 Coloradans died of the substance.

Such poisoning occurs when a person intends to take an ill-gotten drug, as Braden did, but is sold fentanyl under the guise of the requested drug, also known as a counterfeit pill.

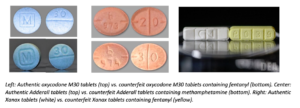

Buyers often assume they are purchasing a generic pharmaceutical pill, but the reality is, the pill is unregulated. Counterfeit pills are made to look reliable like prescription opioids such as oxycodone (Oxycontin, Percocet), hydrocodone (Vicodin), and alprazolam (Xanax); or stimulants like amphetamines (Adderall). Fake pills are easily accessible and often sold on social media and e-commerce platforms.

For American youth, especially young adults on college campuses, the culture of drugs and accessibility to experiment or self-medicate is prevalent. In conjunction with social pressures and the COVID-19 lockdown leading to intense periods of isolation, data from the National Institute on Drug Abuse indicates there have been large increases in many kinds of drug use in the United States since the national emergency was declared in March 2020.

“Fentanyl has nothing to do with being a drug addict,” Wil Lemon, Braden’s childhood best friend, said. “This has nothing to do with being so dependent on a pill that you must take too much of it, to the point you die. That is what you call overdose. This is totally different. Braden wasn’t addicted to pills. He wasn’t dependent mentally, physically, on anything. He one night trusted someone and decided to take a pill and it killed him.”

Though fentanyl is often abused by those struggling with addiction, this narcotic has also seeped into distribution chains for first-time and recreational users, who are unable to survive its potency. Only two milligrams of fentanyl – roughly the size of Abraham Lincoln’s ear on the penny – can be lethal.

Lemon described the months after his best friend’s death as gray, that “every day was gray.”

Accidental overdose or poisoning?

Language is essential in combating this crisis, said Alden and Susan Globe, who lost their daughter Madeline on the night of Aug. 10, 2017.

Madeline was about to enter her senior year at CU Boulder studying communication.

The Globes had a very special relationship with Madeline. Susan Globe called her daughter a miracle baby because she was their only child and born later in her parent’s lives. “She had a curiosity and love and passion and compassion for the universe,” Susan Globe said.

“It is another reason why the loss was so devastating,” Alden Globe said. “She was so smart. Funny. She loved her life.”

Family and friends say Madeline was a global thinker with an ardent sense of global justice. She was very concerned about the environment. From a young age, she opposed the practices at SeaWorld, and while her friends would say “we love Sea World,” documentaries like “Blackfish” solidified her point further. She was drawn to beautiful things, which may explain her post-graduate plans to become an interior designer.

Madeline and her parents loved traveling and skiing together. Her parents were proud of her for studying abroad in Aix-en-Provence, a city in southern France, stepping out of her comfort zone and immersing herself in new cultures.

“To show the irony of the situation, the whole time she was there, we worried about terrorism, attacks, kidnapping, drugging and everything. Nothing happened, she had the greatest time,” Alden Globe said.

She died two months after coming home—a place Alden Globe considered safe for his daughter, a state she had known her entire life and a city she cherished.

“I’m still so baffled,” Susan Globe said because Madeline had no history of drug use. She was considered the responsible one, or “mom,” in her friend group. So, when the police said Madeline died from mixing Xanax and alcohol, that information didn’t seem feasible, said Alden Globe.

Four months later the toxicology report confirmed the pill contained fentanyl.

The last memory Susan Globe shares with her daughter remains vivid: the construction of a new bed frame, an antique piece of furniture from Madeline’s maternal grandmother. With refined taste and a desire to pursue interior design after college, the antique was old-fashioned and idyllic. But in the middle of building the bed frame, one of the legs collapsed and, in college-style DIY, duct-tape ensued. It was a moment in moving, where the exhaustion asks for tears, but gives laughter instead. It was a vivid memory, only days before Madeline was poisoned. In the days and months following her death, emotions of shock and disbelief arose.

Even now, five years later, those feelings still exist for the Globes.

“We still don’t know exactly what happened,” Susan Globe said about the night of her daughter’s death.

Her parents don’t know what house party she went to on University Hill or if she went out for drinks at a bar or what friends she was with. They were forced to reconstruct Aug. 10, 2017, through a series of accounts from CU students who testified, law enforcement who investigated and other medical professionals in court.

Fentanyl deaths are typically labeled as accidental overdoses, which, by definition, means taking more than the normal or recommended amount of a specific drug. But what if the person consuming the drug thought it was a legitimate pill and correct dosage, and instead ends up taking a counterfeit drug?

The question remains contentious. When parents look at the death certificate, labeled as accidental overdose, many exclaim, “my child didn’t have a drug problem.” Alden Globe said he questioned the diagnosis at the coroner’s office. The coroner explained medically, it was a drug overdose, and Alden Globe hesitantly accepted this information. But in the past year, thinking this statement over, seeing more deaths and speaking with other families who lost their kids to fentanyl, Alden Globe no longer agrees with defining the deaths as accidental overdose. Since Madeline’s death in 2017, fentanyl poisoning has nearly doubled nationally from 30,000 deaths to around 64,000 in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The language and the training for coroners, law enforcement and medical needs to be updated,” Alden Globe said.

The common misconception—that fentanyl poisoning stems from the same issue as other drug abuse—harms users who may not realize the street drug they are buying from a dealer contains this lethal compound, like Madeline and Braden.

“It is a poisoning,” Susan Globe said. “They didn’t choose to die.”

Why is Fentanyl being produced?

Criminal drug networks flood the U.S. with deadly fake pills because they are cheap to produce and highly addictive.

Fentanyl commonly comes from Mexico, where it is pressed into pill form and smuggled into the U.S., according to Special Agent in Charge Bill Bodner of the DEA Los Angeles Field Division, who has been an agent for 30 years. Bodner has witnessed the surge in fentanyl first-hand and is aware of increased threat and patterns.

Older traditional drugs—marijuana, cocaine and heroin—take extensive efforts to produce.

To produce heroin, drug organizations must control large areas of land to grow the poppies and then have manual labor to score the poppy plants and scrape the gum off the plants. This process requires control of land and labor, which is time consuming and expensive. In terms of a business, it is difficult to scale heroin production.

Cocaine is primarily manufactured in South America and smuggled into Mexico through Central America—because smugglers deal with multiple government entities and borders and there is a lot of risk, therefore, they add an amount onto the price. It is bought in Mexico with an added surcharge.

And marijuana, which used to be a drug that was a staple and profitable for cartels, has been decreasing in profits after U.S. states began legalization. Marijuana seized at borders has dropped 80% since 2018, according to Bodner.

“One of the things people said is ‘it will deal a blow to the Mexican drug trafficking organizations if we legalize this drug,’” Bodner said. “Unfortunately, it didn’t really deal with a blow – it just caused them to look elsewhere for profit-making drugs.”

Therefore, new profits could be obtained through producing methamphetamines and fentanyl, which are synthetic drugs. Synthetic drugs do not require excessive plots of land or labor. If a producer has the right chemicals, namely from China and India, they only need a laboratory. It became a vertically integrated business model.

“I think a lot of it had to do with Covid-19,” Bodner said. “Think about my business, your business, everyone’s business during Covid-19: it went through a bit of a digital revolution or an online revolution, where everyone was teleworking.”

This period marked a shift in drug trafficking too, and the accessibility of drugs shifted from a physical place to someone’s fingertips on a screen. Kathleen Miles, who works for the Center on Illicit Networks and Transnational Organized Crime, said to CBS News, teenagers are two degrees of separation away from a drug dealer.

“Unless you are getting them from a physician or directly from a pharmacist, it is a fake pill,” Bodner said.

Party culture embedded in college life

Braden and Madeline were both members in Greek life.

Braden was a Pi Kappa Phi and Madeline was a Pi Beta Phi. But along with the philanthropic work and team building, Greek life also fosters a culture of partying, including drinking and drug use, according to 2016 CU Boulder alumus, Brian Keesling.

Keesling was one of Braden’s closest friends since the second grade and they grew up skiing, playing lacrosse and attending school together. Keesling remembers Braden as a “ridiculously funny” person, who was always looking for a smile or laugh, but also a loyal friend who would have deep, meaningful conversations. When college arrived and they were on the same campus, Braden pursued joining a fraternity, while Keesling decided against it. The two remained best friends regardless of involvement in different social clubs, but Keesling was exposed to an outsider’s perspective of Greek life – one of youthful mentalities, where students seemed unaware or did not acknowledge the potential consequences when using substances.

Partying is not exclusive to only Greek life but is described as extremely prominent in such a social setting.

Keesling said, “I don’t know what it is like at other colleges, but I know CU has some pretty serious drug problems as a campus because it is normalized.”

More youths aren’t experimenting, but rather the consequences have changed because of fentanyl’s potency, and parents’ main concern is that one pill can kill.

“Back in 2017, we had never heard anything,” Susan Globe said about the dangers of fentanyl. Susan Globe contacted CU after Madeline passed, being connected with the former assistant dean of students and had several conversations. The dean expressed sorrow and asked to help however she could.

Today with the rise of fentanyl poisonings country-wide, the university has tried to bring awareness, said Kathryn Dailey, associate director of health promotion at CU Boulder. Narcan is available for free at Wardenburg, the on-campus pharmacy, and in efforts to explain the deadliness of fentanyl before St. Patrick’s Day, one of CU’s largest days to party, a series of Instagram stories were posted, and website links were sent to students’ emails. But parents still think the university is not doing enough to protect their students.

Within the Greek community, sorority chapters are not required to hold Narcan in their houses.

“I personally don’t believe it is a clear problem within the chapter facilities,” wrote the internal vice president Kallie Hayes of Panhellenic in an email.

Then again, Hayes said that stocking the life saver, Narcan, “is a great idea. I can encourage risk officers to get some from Wardenburg.”

Moving forward, Hayes said she will require each chapter to present a risk presentation to their chapter members before they host a formal, which is a social-date event.

According to Michael Smith, an advocate for Interfraternity Council on the Hill—the independent and non-university affiliated fraternity organization consisting of 20 fraternity chapters—each chapter has its own drug and alcohol policies. Therefore, Narcan may be required by different national affiliations. At CU Boulder alone, fraternities are required to abide by their 911 program. The program requires their members to call 911 if any symptoms of distress arise and they will receive protection under The Good Samaritan Law.

Advocacy groups strive to educate

Voices for Awareness Foundation, led by Andrea Thomas and D’Ann Hopkins, is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization based in Grand Junction working to bring awareness to communities regarding illicit drugs, fentanyl and self-harm.

Thomas lost her 32-year-old daughter Ashley to fentanyl poisoning on June 11, 2018. For years Ashley suffered from chronic pancreatitis and would often go into stays at the hospital, receiving tramadol or oxycodone to subside the pain. Yet, pain pills made her nauseous, so she would only take half at a time. After losing private health insurance, she went on Medicaid, and when couldn’t receive a proper prescription any longer, her boyfriend gave her what he believed was oxycodone. Ashley took half of the pill, but it wasn’t regulated and contained fentanyl, killing her almost instantly.

It is not easy to use a deceased child or sibling’s name, pictures and experiences as an example, Thomas said, but it may be essential in protecting other young people unaware of counterfeit pills’ 40% chance of containing fentanyl.

“What’s kept me going is seeing the increase in people dying every day,” Thomas said, “And how could I stop now? It becomes more than my daughter.”

Thomas’s advocacy expands across all sectors of fentanyl—education, supply reduction and legislation. The consistent principle in each advocacy lens is addressing stigma around death by fentanyl. Thomas explains it is not the typical drug user overdosing anymore, nor is it the old paradigm drug dealer on the street corner. Dealers are now connected to users through smartphones and social media.

“These are not the drugs of five or ten years ago,” Thomas said.

This is why Thomas, along with Gottsegen and the Globes, testified before Colorado lawmakers regarding anti-fentanyl legislation in the 2022 regular session.

Gaps in the justice system

“Justice is a long process,” Gottsegen said.

For Braden’s case, it took almost three years to get a federal prosecution. For other families, legal action was never an option – law enforcement was unable to track down the dealer or district attorneys couldn’t prosecute because of the lack of statutes in Colorado – and for some, it is ongoing.

“We were fortunate the police chose to follow up and begin an investigation in our case,” Alden Globe said. “Not every parent who loses a child to fentanyl gets a follow-up call back.”

Today, there is an effort to strengthen protocols around investigating fentanyl-related deaths: HB22-1326 – Fentanyl Accountability and Prevention, which was signed into law by Gov. Jared Polis on May 25.

A month before the bill was signed, a crowd of witnesses—supporters and opposers—filed into room 217 at the Colorado State Capitol at 1:30 p.m. on April 17, they prepared their 2-to 3-minute witness testimonies for the House committee. The families in the crowd came to realize they are not alone, left angry and disoriented by fentanyl poisoning. Of those families included Andrea Thomas, who was dressed in a black blazer with a t-shirt underneath with the words VOID, a fentanyl-awareness organization based in California. VOID stands for Victims of Illicit Drugs. Tami Gottsegen filed into the second row, facing the committee, with her mother, brother, husband and stepdaughter. Susan Globe joined over Zoom.

As the room settled into silence and murmurs, the House Speaker addressed the committee. The room was filled to its maximum capacity. Remnants of Covid-19 were visible as some noses and mouths were covered with polyester-blended or cotton masks. And with the heat of so many bodies and overflow in the halls, the windows were cracked on the east side of the room, allowing fresh air to flow. The three major paintings in the room reflected Colorado landscape and history, leading to this moment. A moment where legal jargon fills the air while families wait to share their stories, often shaking their heads in agreement or disagreement with opinions presented.

Andrea Thomas waited eight hours and 57 minutes to testify. Susan Globe waited 12 hours and 29 minutes. And Tami Gottsegen would have waited over 13 hours to testify, if her family stayed past 3 a.m., but exhaustion and frustration overwhelmed.

After 12 hours of passionate discourse, the motion passed.

–

“This bill is a huge step forward for holding accountable those who are pedaling this poison,” District Attorney Brian Mason for Colorado’s 17th Judicial District, which serves Adams and Broomfield counties, said. “Right now, in the state of Colorado, we don’t have a distribution of fentanyl causing death statute. That means I, as a prosecutor, if I have someone who has distributed a drug with fentanyl in it that causes someone to die, I can’t hold them accountable for that death. This bill will allow me to do that.”

Currently, Mason’s district has the largest, lethal incident in the U.S.—five adults died by fentanyl-laced cocaine on Feb. 20. Mason said this incident will likely not be the largest for long.

“No drug is safe right now,” Mason said. “We are finding it in cocaine, we are finding it in heroin, we are finding it in meth, we are finding it in oxycodone, and in limited circumstances, we’re even finding it in marijuana.”

HB22-1326 was one of the most controversial of the concluded session, as the crisis involves an intensely intricate and detailed web of stakeholders extending beyond the dealer, who is simply a middleman. But Sen. Cooke said this bill is the first step to crack down, adding that sheriffs and law enforcement need new tools to hold dealers accountable and strengthen the political penalties for dealing fentanyl.

The new law heightened felony charges for possession of 1 to 4 grams of any substance containing fentanyl; harm reduction programs to help people treat their addictions, including medication-assisted treatments in jails; access to education programs; widespread availability to Naloxone and testing trips; criminal investigations into deaths due to fentanyl; and continued tracking of deaths by fentanyl.

Although Gottsegen and Thomas don’t think the bill is strong enough, especially as only 2 milligrams can be deadly, they both said it is a step in the right direction to save lives.

Healing after loss

For Gottsegen and the Globes going to court, hearing a verdict and putting the dealer in prison is only a part of progress.

The complex process may serve justice but does not holistically heal because families and friends will never forget their lost ones’ impact. They now notice the empty chair at the dinner table; they now have an aching over holidays and anniversaries.

Within each story of loss to fentanyl, parents express a desire to protect each of their kids and tell their story. Their children are no longer here to defend their legacy— it has fallen to their families to educate others, while simultaneously grieving the life most essential to theirs.

“You never get over grief, but you can learn to move forward with it,” Alden Globe said. “There is a hole in your heart now and it will never get smaller, but you can work to make your heart bigger. And how do you do that? By honoring the memory of your lost one and by trying to help other people.”

For more information on fentanyl, check out these resources: United States Drug Enforcement Administration’s factsheets and CU Boulder’s Health & Wellness Services.

About the author

Hannah Prince is a 2022 graduate of the University of Colorado Boulder. She majored in journalism with minors in English and business and was former newspaper editor-in-chief of The Bold. She currently works for ABC News Investigative Unit in New York, NY. She can be reached at hannahjoprince@gmail.com.

Alec Levy-O’Brien is a 2022 graduate of the University of Colorado Boulder. Studying Journalism and Sports Media, he spent two years at the CU Independent working as a photojournalist covering sporting events and breaking news. He currently works as a professional cycling photographer out of Boulder, Colorado. He can be reached at alevyobrien@gmail.com