The Hope and History of Queer History: An Educational Tradition and Modern Challenges

On October 31, 1969, TIME Magazine published a lengthy analysis on homosexuality, concluding that, “While homosexuality is a serious and sometimes crippling maladjustment, research has made clear that it is no longer necessary or morally justifiable to treat all inverts as outcasts. The challenge to American society is simultaneously to devise civilized ways of discouraging the condition and to alleviate the anguish of those who cannot be helped, or do not wish to be.”

Jumping to the present day, the charge of that publication is foreign and nearly shocking. Where a mere fifty years ago, individuals lost their livelihoods for the mere suspicion of being gay, today, Americans overwhelmingly support the legal protections of gays, lesbians, and bisexuals to have consensual relations and integrate themselves into the public eye. In 1969, when TIME’s homosexuality article was a centerfold article, the question of same-sex marriage was still decades away. Today, the 2015 Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges stands as precedent for marriage equality.

In this same zeitgeist that now tolerates, perhaps embraces, queer rights, the last year has shown increased hostility towards gender expansive people. Throughout 2021, lawmakers across the United States have moved to bar transgender youth from accessing school functions, or in other cases, medical care. Within the last month, the unapologetic usage of transphobic language by performer Dave Chapelle has led to continued discussions about how Americans view and treat gender expansive people.

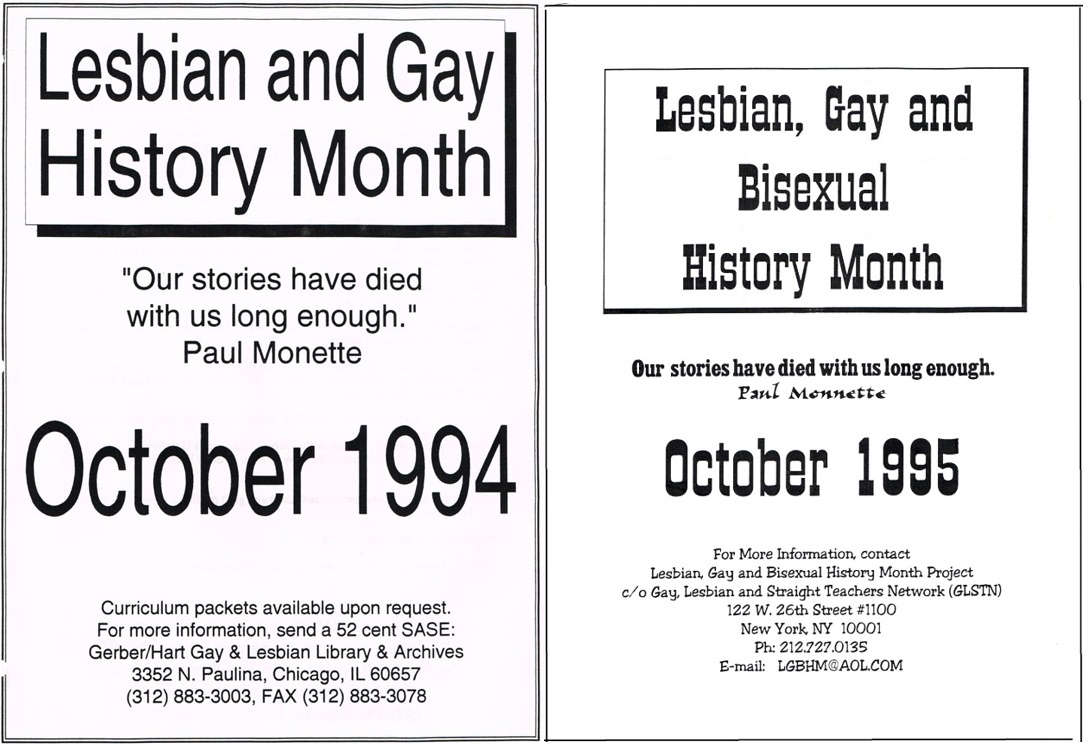

October is LGBT History Month, founded in 1994 by Missouri teacher Rodney Wilson. The tradition follows the continually evolving legacy of America’s queer civil rights movement: from the secretive backrooms of The Mattachine Society to present day conversations. Modeled after Black History Month, which takes place in February, Wilson describes LGBT History Month as a way to allow students access to history of themselves and others.

Wilson created the tradition in a period of tumult for his personal and professional career. An openly gay man, everywhere but his teaching job, Wilson came out in March 1994 to his students through a lesson on the Holocaust. Connecting the lesson to himself, Wilson highlighted to that class he would have had a pink triangle in Nazi Germany: a negative marker of homosexuality from the Nazis.

News of Wilson coming out quickly spread across his school, then ballooned out to national media. As this happened, Wilson was already months deep in creating a national committee to establish Lesbian and Gay History Month, as his profile jumped to national attention.

Having already taught queer history and making his own place in it, Wilson pressed forward in 1994 to make LGBT History Month a reality. After months of organization with multiple scholars, educators, and supporters across the country, that reality came to pass with multiple proclamations from mayors, governors and other officials who affirmed the need to expand knowledge on queer history.

And from 1994, the tradition has continued, expanding to also include bisexual, transgender, and queer people broadly in its mission of historical education. “[W]e must intentionally, consciously, deliberately study the lives and recover the stories of the entire spectrum of our incredibly diverse and rich community. The rainbow is for everyone,” Wilson stated.

Wilson further highlighted the need for people to be watchful, since progress frequently has backslides. Even while Americans have visually made leaps and bounds towards equality since 1994, total equality remains elusive.

Wilson highlighted that in regards to queer history “[t]here are threats to equality of resources and research.”

In September 2021, officials in Missouri pulled a historical exhibit on LGBTQ+ History in Kansas City at the Missouri State Museum, after a handful of complaints from legislative officials. Also in September 2021, an Oregon school board voted to extract symbols related to social justice from classrooms, helping censor ideas and raising new ideas of what content can be mentioned in learning environments.

Wilson discussed a queer 22-year-old teacher from Missouri, who in September resigned after school officials prohibited displays of the Pride flag in classrooms.

“This young man was born in 1998. I taught at that high school 90 to 97. He wasn’t even alive, when I was teaching there, I thought this issue was also resolved,” Wilson said.

Other events in recent months also show the continued challenges for queer visibility in educational spaces. In July of this year, a transgender magician canceled a performance at a Wyoming library after multiple threats from local residents falsely dubbed her a pedophile because of her trans identity. That same library in September faced backlash from aggrieved residents for placing LGBTQ+ focused books in areas for children and teens to access.

In the Boulder-area, St. Vrain Valley School District severed ties with A Queer Endeavor, an organization that educates teachers on LGBTQ+ topics through the lens of equity and justice. That relationship ending came after a handful of parents complained about A Queer Endeavor’s presence being anti-parent and inappropriate at-large.

At a recent St. Vrain Board meeting on September 8, one parent equated drug usage by minors to students exploring their gender identities. “Parents have a right to know what their children are doing at school. If my child was going to school and going out on ‘Smoker’s Hill’ and smoking pot every day, I think somebody would tell me that at parent-teacher conferences. If my child is going to school and changing their clothes from one gender to another, I would want the school to tell me that, and I don’t think it should be a secret.”

Another parent commented, “While I do agree that students do need support, LGBTQ+, that should be a parent’s choice.”

In spite of these challenges, Wilson offered aspirations for the coming years: “These threats notwithstanding, I’m hopeful that we’ll continue to meet these challenges and carve out more spaces for our community’s history. More colleges will offer gender and sexuality studies. More American History 101 classes will include all the history, including ours[, LGBTQ]. More community and academic groups, and secondary schools and colleges, will do something special for October’s LGBT History Month.”

Wilson’s thoughts underscored that historical progress is not linear. In the movements for securing civil rights for gays, lesbians, and bisexuals – challenges are constant. In 1992, Colorado voters passed Amendment 2: a measure that barred the state or any local polity from issuing legal protections on the basis of sexual orientation. That referendum passed only after victories in Boulder and Denver that ensured queer people in those municipalities had legal protections. It was not until 1996 that the Supreme Court case Romer v. Evans reversed Colorado’s Amendment 2, but not before years of turmoil and anguish for queer Coloradans.

2020 Pultizer Prize finalist Eric Cervini, in a separate interview, reflected on how to continue expanding knowledge on queer history. Beyond mainstream knowledge about events like the Stonewall Riots, Cervini found the challenge of queer history is accessibility, or the lack thereof. Cervini cited how universities and research journals often dictate what information is acceptable and have financial and social barriers to access what research is permitted.

“It’s up to the researchers to also take that extra step of once you publish in an academic journal, or you publish your monograph, then taking that information and making it accessible… maybe write an op-ed, or maybe you publish an infographic on Instagram or on social media. Or you publish a TikTok that kind of explains it in one minute… There is some responsibility on all educators of making their work as accessible as possible,” Cervini said.

Cervini has a TikTok account where he posts queer history stories and tidbits.

The United States has made strides in embracing and recognizing the role of LGBTQ+ people. From calls to discourage queer people from embracing their identity, Americans have changed societal norms and laws that embrace equality and safety for more people. Yet, challenges remain all across the country: from rural areas of Missouri to more progressive areas, like in Boulder County. LGBTQ+ history and its associated month are ways to ensure progress remains steady, regardless of calls for censorship or discrimination. Yet, for that work to be successful, it must have broad influence and work beyond institutional boundaries.

The new challenge to American society is simultaneously to devise civilized ways of encouraging equity and justice and to alleviate the historical anguish of how American society has treated LGBTQ+ people.