Evolution in the Eyes of a Global Pandemic

A woman sits at a small table covered with at least 20 test tubes, plastic bags and other tools. A cafe lounge doesn’t seem like the place to test samples but she must know what she’s doing. The cafe rests inside the large and empty atrium of the Jennie Smoly Caruthers Biotechnology Building at the University of Colorado Boulder. Opposite the woman is a sign that reads,“Fresh blended smoothies.” The cafe has been closed thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. There is no telling how fresh those smoothies will be once it reopens.

The woman is not who I’m there to meet, but I’m fascinated by her. I have no idea what she’s doing, yet I’m quick to question her methods. I fear the cafe air is contaminating her samples. Before I gather the courage to ask what she’s doing, I see who I’m there for: Vanessa Bauer.

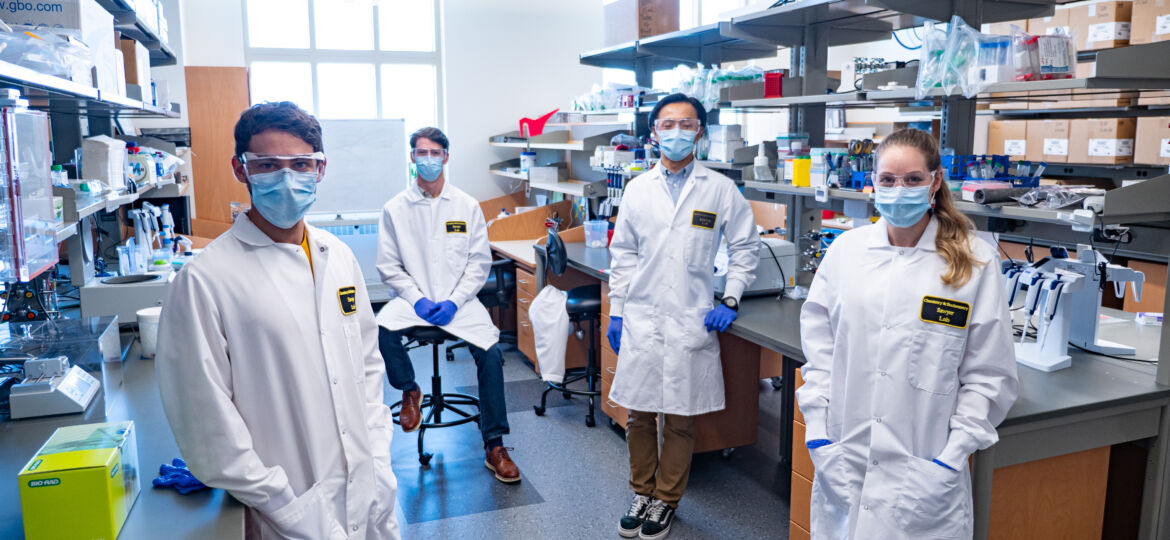

Bauer is wearing typical lab attire: full length pants and closed-toes shoes and, a clear sign of the times, a mask. On her shirt is an image of DNA along with the acronym, GGD: the Genetics Genomic Department at Cornell where Bauer worked for 20 years. Now she works in the Sawyer Lab that studies the spillover of animal viruses, when viruses make their way from their original animal hosts into human bodies. The most recent spillover virus? SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus’ source.

Bauer calls COVID-19 the “perfect virus” since it can spread before hosts even know they’re sick. COVID-19’s goal—if one can say a virus has goals—is to spread its DNA around like Zeus—killing its host would be suicide. Yet reports about new variants have the public panicking over the possibility or a fourth wave. This distress is understandable since we’re dealing with a virus that’s killed millions of people worldwide. Coronavirus anxiety has facilitated the spread of false information about the virus. Being a novel virus, it’s understandable confusion clouds the public’s knowledge of the coronavirus. What’s inexcusable is the public’s steadfast misconceptions about evolution. Evolution is the building block of natural phenomena. Falsely held ideas about it need to be cleared up.

…

First thing’s first, evolution doesn’t have a pre-set trajectory: there is no higher plan¹. Us humans weren’t meant to evolve, we happened to evolve. It seemingly worked out for us, but the dinosaurs probably thought it would work out for them too and look how they turned out. According to Scott Taylor, PhD, people have this idea in their heads that things “evolve to be something more complex.” But there is no rhyme or reason to evolution: it’s a random process with an equal probability of helping or hurting a species.

The mechanism behind evolution is genetic mutation. Mutations are accidents that can be beneficial, deleterious or neutral. A beneficial mutation would help an organism become more fit, allowing it to continue to pass on its genes to offspring. The fastest wildebeest will have fast babies that survive because they always outrun a lioness. A deleterious mutation would hurt an organism’s chances of survival, making it difficult or impossible to pass along its genes. Small baby turtles that are picked off by seagulls before making it to the ocean never even get the chance to lay eggs of their own. A neutral mutation wound neither help nor hurt an organism’s chances of passing on its genes, just like how having blue eyes doesn’t alter someone’s chances of finding a lover—or maybe it does…

As for COVID-19, a deleterious mutation causes it to kill its host before spreading. A beneficial mutation for COVID-19 causes the virus to spread without off-ing its host. The hope is that SARS-CoV-2 will eventually evolve to have a low mortality rate, which is a good sign for the virus and for us hosts. Unfortunately, we can’t be sure this is the path the virus will take.

…

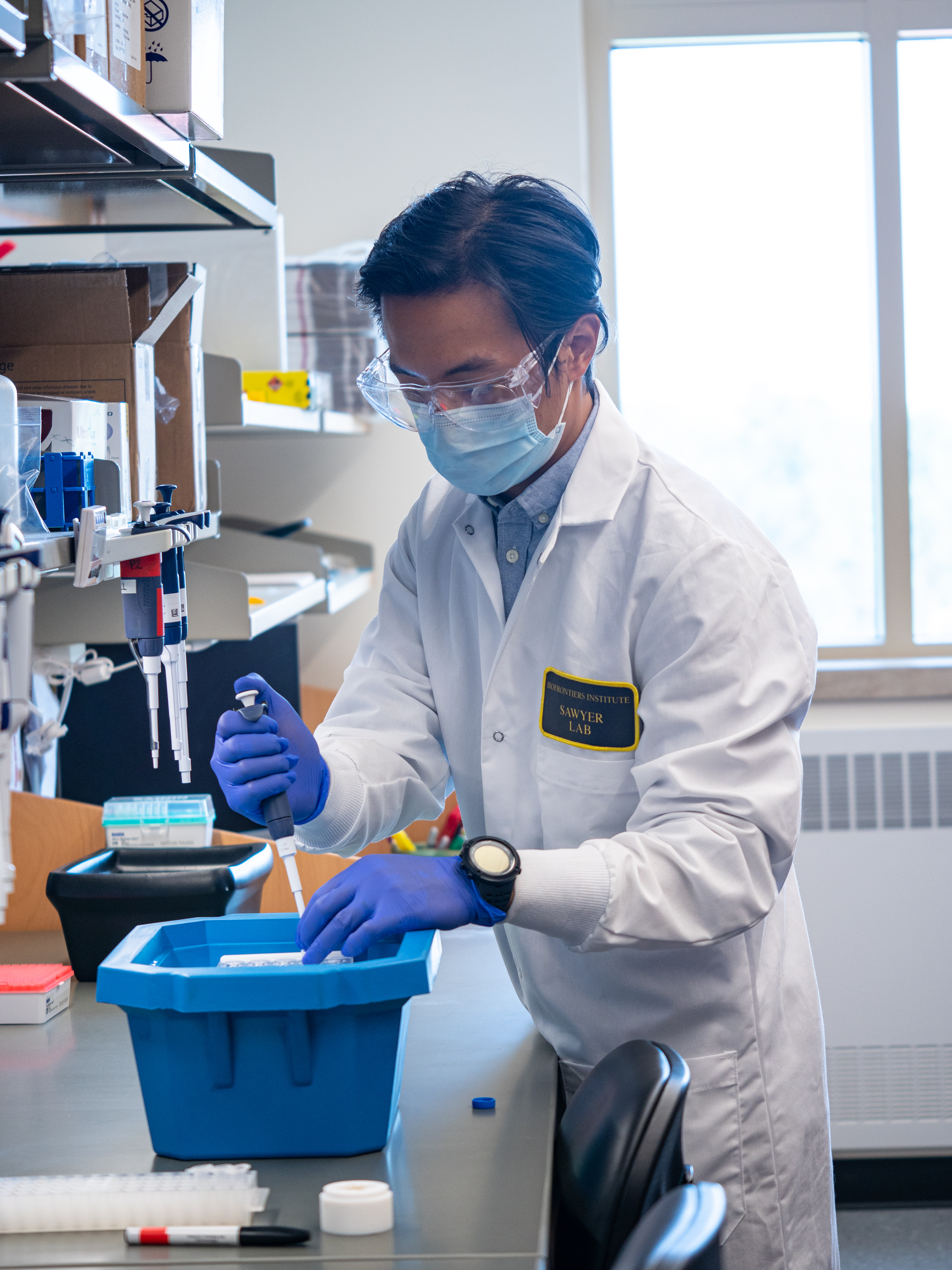

Heading to the Sawyer Lab, we walk down a series of hallways and pass through several doorways requiring keycard access. Ten feet up, the main hall of the Sawyer Lab is coated with posters of past research. Bauer stops next to a bookshelf labeled with employees’ names; she takes some things from her bag and deposits them onto her shelf. Food and drink aren’t allowed in the lab.

Inside, we’re greeted by racks of lab coats, large coolers filled with samples and an array of all different sized test tubes. The lab seems a bit chaotic for a workspace filled with infectious viruses, but I assume (and hope) the scientists have a method behind their madness. The end of each bay ends in a desk next to a small window. The sunlight that does reach inside, is doing a surprisingly good job at keeping a few plants alive.

Bauer leads me to a much more secure area where scientists work with highly concentrated samples of different viruses. This room stores two towering biosafety cabinets that filter air, meant to protect the scientist and her sample. Everything leaving this room, besides humans, passes through an autoclave, a giant machine built to sanitize everything that passes through.

Bauer’s reaction to COVID-19? “Not that surprised,” she chuckles. She tells me her coworker Cody Warren, PhD, had given a lecture in the fall of 2019 on the possibility that other animal coronaviruses could emerge in humans again, like SARS and MERS did in 2003 and 2012 respectively. His main point? “It’s not a matter of if, but when.” Sounds like Dr. Warren has a job as a psychic if this whole science thing doesn’t work out.

Speaking with Dr. Warren helped clarify that coronaviruses are actually a family of viruses: SARS-CoV-2 is a new member of that family, a term used by scientists to describe closely related organisms. “The most closely related virus [to SARS-CoV-2] is in bats and it’s only 96% identical,” Dr. Warren explains. Stacey Smith, PhD, explains the virus can be transmitted to humans because they share a common ancestor, resulting in similarities in their genetic makeup, making it easier for the virus to jump between species.

It’s hard to imagine an evolutionary relationship between humans and bats, but it’s true. In fact, everything alive today shares a common ancestor—which is not the same as myself and the cousins I occasionally forget sharing grandparents—it’s an organism that no longer walks this earth but gave rise to modern species. It’s like a fork in the road: as one road ends, two more split from it. As for bats and humans, this means both species can trace their lineage to the same organism living millions of years ago.

This concept that humans and bats are related contradicts what many believe about humankind’s evolution. The image that comes to mind when we think about evolution makes scientists cringe: a chimp gradually standing upright to walk on two legs, losing body hair and becoming a modern human². Like bats, apes and humans can trace their ancestry to a shared ancestor… no chimps abandoned their species to become humans. It can be easy to think we came from our ape friends because we look alike, but these are just characteristics both species held onto. We don’t look like bats, but our similarities are there, under the surface in our genetic code. It’s time to retire the image of a timeline where a chimp becomes a human and replace it with a tree, where one common branch splits into two.

…

Bauer finishes telling me a story about confronting a man in a grocery store who wasn’t wearing a mask. His reason? The “lack of oxygen” and irritation wasn’t worth it.

And did you tell him you’re a scientist who studies viruses? I ask.

Yeah, I did.

And he didn’t care?

No, he didn’t care, she laughs.

She is very aware of the gap in people’s understanding of scientific concepts that the pandemic has highlighted. She’s frustrated at what she calls “a fault of science,” or the lack of communication with regular folk. In the pandemic’s early days, Bauer felt scientists believed “people weren’t ready” to handle all the information. This rift in communication has since caused problems with people’s understanding of COVID-19. “In science, you realize you made mistakes… You make claims and find out you’re wrong,” Bauer says referring to the CDC’s original claim that we shouldn’t wear masks. “People latched onto [that].’”

Not believing in masks is just another falsehood the general public holds onto about science. Dr. Taylor wants to make clear that evolution is real, it’s not a theory. At a young age, students learn about Darwin and his theory of evolution. Darwin wasn’t theorizing that evolution happens, he saw it in front of his eyes in the Galapagos, and his all too familiar findings hypothesized how evolution occurs. Like gravity, we know it’s real because if you drop a pen it’s going to drop to the Earth. What scientists are still theorizing is how it exactly works, how evolution works. We know humans and apes, and humans and bats, and bats and apes are related. We are working to discover how they are related.

As scientists continue to discover unknowns about our world, the least the public can do is accept they might not know everything. We’ve been holding onto falsehoods about evolution for too long. It’s time to unlearn evolution has an end goal, to unlearn that humans came from apes and to unlearn that evolution is a theory. Letting go of these distorted views of evolution won’t guarantee our survival as a species, but it’s not a bad idea to improve our knowledge while we’re here. Truth is, there was a time before we evolved and there will be a time when humans diverge into new species.

Author’s Note: Interviews for this article were conducted over Zoom and in person. Exact dialogue in this article is indicated by the use of quotation marks. Approximate dialogue is indicated by the use of italics. Although wording may not be precise, approximate dialogue has been kept as close to reality as possible, making sure the meaning of the conversation is as it was in real time.

1An entire paper could be dedicated to Evangelical Protestants’, especially white Evangelical Protestants’, relationship with evolution and the effects on society. According to a 2013 Pew Research Center study, 32% of Americans believe evolution is due to natural processes, 24% believe the process is guided by a higher power, and 33% reject the concept of evolution entirely. Deborah Whitehead, PhD, attributes that middle third to a “desire to affirm modern scientific knowledge but hold onto a fervent religious faith.”

2Specifically, Dr. Taylor and Dr. Smith brought this image up as something they can’t stand when it comes to what the public thinks about evolution. Even Wikipedia points out that this image “wrongly” implies that evolution is “linear and progressive.