When Queer Women in Boulder Fought Back

By Cayden Stice

Writer’s note: Where not linked, information for this article comes from the oral history collection of Cayden Stice, compiled from September 2020 to January 2021. These oral histories will also be used in a greater project by Stice, a thesis looking at the queer political history of Boulder, Colorado in the late-twentieth century, to be completed in April 2021.

When Kat Morgan moved to Boulder, Colorado in the early 1980s, a town known for its liberal reputation and progressive outlook, one notable absence stood out: the city had yet to adopt sexual orientation into its Human Rights Ordinance, which would prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in housing, employment and public accommodations, whether gay, lesbian, bisexual, heterosexual or another identity. Curious about the lack of protection, Morgan pursued the Boulder City Council, wondering where and how to go about adopting such a provision. As she met with individual members, it became clear that none had the political appetite to help. Though many were supportive of her initiative privately, council members feared for their political safety should they get involved, citing the political furies of the 1970s.

In 1974, the idea of adopting sexual orientation into the municipal anti-discrimination codes inflamed the community, leading to the political downfalls of those who most supported the measure. In late 1973, the City Council passed Boulder’s Human Rights Ordinance into law, with the consideration of also adding sexual orientation into its wording (referred to as “sexual preference” in this era). Yet, as political conservatives in the city caught wind of this, a brouhaha commenced. In February 1974, hundreds turned out to lash out at the council, claiming that homosexuals were turning Boulder into a modern Sodom and Gomorrah, with one speaker, Hilma Skinner, fearing the city would transform into a “sex deviate mecca” named “Lesbian-Homoville.” Pro-gay activists also turned out, many fashioned with lavender armbands in solidarity with LGB people. As a result of the backlash, the City Council sought to ease the nerves of the city, placing the sexual orientation component of the Human Rights Ordinance to a referendum, so voters could directly decide on the matter.

During the spring of 1974, the campaign for what became known as the “Sexual Preference Amendment” (SPA) spiraled into contention over the humanity of gays, lesbians and bisexuals. A “yes” vote for the amendment added sexual orientation to the Human Rights Ordinance, while a “no” vote denied that possibility. Though anti-discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation did extend to heterosexual people, the mainstream thought in Boulder was that the matter centered around the views of LGB Boulderites. Yet, though the amendment situated itself on the rights of gays and lesbians, the social climate of Boulder made it difficult to come out of the closet and publicly campaign in support of the SPA. Because of this regressive atmosphere, Boulder Mayor Penfield Tate II, a heterosexual ally who authored the amendment, became a focal point of ire among religious conservative opposition. Tate was Boulder’s first, and to date only, Black mayor, prompting his opponents to lob both homophobic and racist insults his way (including phone calls to his house, laced with profanity and slurs).

Come May 7, 1974, the special election for the SPA drew a record turnout of over 20,000 voters (of roughly 40,000 registered) for a non-November election. By a decisive 2-to-1 margin, Boulder voters defeated the SPA, preventing sexual orientation from being included in the anti-discrimination law in the city. Across the country, Boulder was the first-in-the-nation to attempt this popular vote method for adopting this civil rights protection. Though pro-gay activists had hoped for student turnout from the University of Colorado Boulder to bolster the yes-campaign (considering polls indicating high support and eighteen-year-old voters becoming enfranchised with the 26th Amendment in 1971), this turnout did not manifest.

For conservative activists, stopping the SPA was not enough. Instead, they sought retribution against supporters of the amendment, pointedly towards Mayor Tate and City Councilman Tim Fuller, who had also endorsed and lobbied for the measure. After gathering the required amount of signatures, conservative activists led Tate and Fuller to a recall election for their positions. While Tate narrowly survived the recall efforts, Fuller lost his seat on the City Council, ceding it to a more right-wing Boulder resident. As Fuller had campaigned for the SPA, and amid his recall battle, he did so as a closeted gay man: a cruel irony against someone who sought better protections for gay people, now losing his own ability to politically fight on the council. A decade later, new members of the Boulder City Council had not forgotten the treatment towards Tate and Fuller and thus became hesitant to help out Morgan and LGB activists in new pursuits.

After learning this history, Morgan turned to her friends in local queer social groups, eager to change the city law and expand civil rights for LGB people. A group of lesbian-identified feminists emerged, creating the Equal Protection Coalition, dedicated to overcoming the history that harmed LGB people in 1974 and ensuring passage of a similar amendment by voters. Among these activists were Morgan, Casey Gardner, Nancy Grimes, Sue Larson, Marcia Munson, Prudence Scarritt, Tara Tull and many others who filtered throughout the campaign. Many of these women were CU Boulder students. As the AIDS crisis impacted many gay and bisexual men, it was queer women in Boulder who took the torch of civil rights to ensure protection for themselves and their brothers. From 1985 to 1987, the coalition led educational workshops to inform the Boulder public about the harmful effects of homophobia, guiding participants through activities to illustrate the degrading ways society acted towards LGB people: whether in a work environment or while holding the hand of a loved one in public. The coalition also led efforts to collect enough signatures to get on the ballot, a hard-fought endeavor that took months to achieve throughout early 1987.

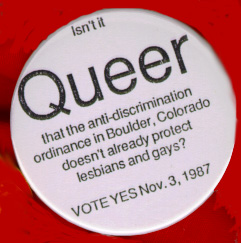

Yet, the coalition did manage to get enough signatures, letting the amendment (Ballot Measure #1) go to the November ballot for voters to again decide the fate of anti-discrimination law for LGB residents. Recognizing the challenges of 1974, though, the coalition sought a quieter campaign, not drawing as much attention to the media, thus hoping the most vocal anti-gay activists would not muster strong motivation and turnout. Instead of conservative opposition taking the power of the narrative, the coalition’s activists wanted to keep the ball for themselves. While national queer-oriented organizations, including ACT UP and the National March on Washington, led pickets and vocal efforts, the coalition already discovered the Boulder City Council was a lost cause for enabling change, and thus needed a minimal campaign to ensure a better chance at passing (opposition did foment, nonetheless, albeit to a significantly less degree). Despite Boulder having a left-wing reputation, the older generations of the city maintained their conservative sway, compounded by the relative apathy among student voters to turnout.

For each of the women involved with the campaign, different motivations drove their activism. For Kat Morgan, she found an unacceptable lack of protection and sought to better the environment for herself and other queer Boulderites. For Casey Gardner, she needed job security, as she worked in social services, where being out would almost certainly cost her job and income. For Sue Larson, a Boulder native who witnessed the 1974 debacle, she wanted her city to work and protect her, rather than idly waiting in the shadows of the closet. For many of these organizers, they also sought to bring empathy and raise consciousness about gay, lesbian and bisexual struggles. Through the educational workshops, they hoped that even if the ballot measure failed, at the very least Boulderites would have more exposure to queer people and let down their barriers of fear and stigma against LGB people.

As the Nov. 3, 1987 election approached, the coalition continued campaigning for the measure, and some members also went to attend the Oct. 11, 1987, National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Come election night, activists in the coalition gathered in an apartment, with varying levels of anxiety about the outcome. For Larson, an electoral win was just another win atop the educational successes. For Morgan, the founder of the group (alongside Gardner, the only other remaining original member), years of work culminated in this one night. Shortly after midnight, results came in: the coalition won. By a margin of less than 300 votes and turnout around half of what it was in 1974, sexual orientation became protected in Boulder law.

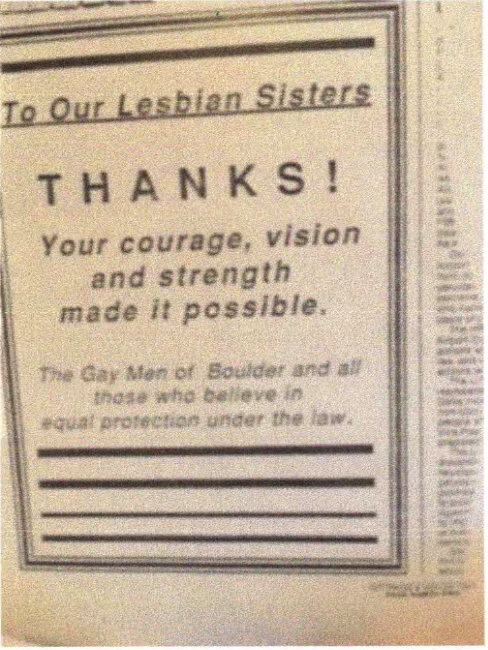

Following this victory, the LGB population of Boulder experienced a period of great optimism and excitement. A collective of gay men published an advertisement thanking their lesbian sisters for the endurance to pass the measure. More people came out of the closet, now having protections in place to fight back should issues arise. For the activists of the coalition, many continued in their efforts, lobbying for greater queer visibility and acceptance across the city and Colorado at-large. Eyeing the success of the Equal Protection Coalition (EPC), Denver activists launched the Equal Protection Ordinance Coalition (EPOC), and mimicked tactics by the EPC to also find success in 1990. In the same period, pro-gay anti-discrimination efforts in Colorado Springs, a conservative hub of the state, created more tension among the state’s religious conservatives. As a result, backlash grew against the growing spread of LGB protection, leading to the formation of Colorado for Family Values (CFV), an antiliberal group determined to eliminate all legislation protecting queer people in the state. In 1992, CFV’s campaign, Amendment 2, proved successful, overturning the work of Boulder’s EPC, along with other local government’s similar legislation. In 1996, the Supreme Court overturned Amendment 2, Romer v. Evans, reinstating the previous work by groups like the EPC. Nonetheless, in these four years, the spirit and optimism of LGB people had diminished, also in light of other harmful policies including 1993’s Defense of Marriage Act and 1994’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell directive.

Yet amid the higher-powered forces that reversed the EPC’s work, it is necessary to recognize the impact of the small group of women (who, at times, had the assistance of men throughout the community), none of whom had extensive political experience. Their commitment to justice and anti-discrimination expanded the ability for lesbian, gay and bisexual Boulderites to live comfortably and demonstrated that their community was driven and motivated. Though 1974 was a hiccup for queer people in the city, the strategic efforts of the EPC challenged that historical legacy.

* * *

To learn more about the queer history of Boulder and Colorado at-large, read The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle by Lillian Faderman, A Look at Boulder: From Settlement to City by Phyllis Smith and “Movement and Countermovement Dynamics Between the Religious Right and LGB Community Arising from Colorado’s Amendment 2” by Lauren L. Yehle.