Editor's Note

Dear Readers,

Hello and welcome back to The Bold Magazine! I hope you had a wonderful new year and that the beginning of 2021– given its ups and downs– has treated you well. Today’s magazine publication date, February 1, marks the first day of Black History Month in 2021, a month in which recognition is given to the influential words and actions of Black individuals and movements that have progressed and shaped the U.S. As such, I wanted to impart some information about a powerful woman who’s inspired me throughout my life: Maya Angelou.

Born as Marguerite Annie Johnson in 1928, Angelou was an influential author and poet, a singer, a civil rights activist and much more, filling the world with her wisdom and creativity through various mediums. She’s written numerous autobiographical books, such as I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, describing her life as a Black woman as well as volumes of poetry– including the Pulitzer Prize nominated Just Give Me a Cool Drink of Water ‘fore I Diiie— that continue to entertain and educate readers today. One of my favorite poems, “Still I Rise,” offers a thought-provoking story of a Black woman who continues to persevere through, and to rise to, any situation. She writes:

“Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.”

Fighting for civil rights, Maya Angelou worked alongside Martin Luther King Jr., who asked her to serve as the northern coordinator in 1959 for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In addition to her civil rights work, she pursued media-based projects and became the first Black woman director in Hollywood. Her achievements did not go unnoticed, as she was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 2000 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in 2010. However, as a Black woman, she faced much adversity throughout her life.

The theme for this magazine issue, “Our Intersections,” is centered around the topics of diversity, equity and inclusion– controversial terms that have come to be debated, questioned and a call to action for people and organizations across the U.S. In light of the police brutality and Black Lives Matter protests that frequently occurred during the summer of 2020, it’s important to recognize the influential individuals who have dedicated themselves to fighting for equality and freedom for all– individuals like Angelou.

Discussing racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and other forms of discrimination can seem messy, as though they are topics to avoid because they are too much– too personal, too complicated, too conflicting, etc. Even defining what diversity and equity means and what it should look like is a complicated, multilayered conversation.

However, while these are hard conversations, they are critical conversations, as they can initiate progress towards creating a society where people are not judged based on the color of their skin, their gender expression, their sexuality, but rather on their character. The stories in this magazine touch on: art as a method of activism, the importance of the Multicultural Leadership Scholars organization at CU, a profile on a refugee woman who is now a Colorado teacher, the influence of racial diversity on one’s future, the difference between cultural appropriation and appreciation and a self-reflection on the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The title, “Our Intersections,” touches on the idea of intersectionality, and that while we all are unique in some ways, we are also very much the same in others. Each of us have a mixture of different identities that may take us on different paths at times, but there will always be moments where we cross and meet once more.

I want to thank all of the writers for their hard work and vulnerability in sharing their stories, as well as those who were interviewed in these stories that offered their own experiences. This issue prompts me to think more about the responsibility I have– as a student, as a journalist and as a person.

I hope this magazine issue offers ideas and insights that are powerful to you and something you’d like to share and discuss with others. If you have any questions or interest in participating in The Bold Magazine, please feel free to contact us at thebold@colorado.edu or contact me at tayler.shaw@colorado.edu.

And to end, I leave you with this excerpt from Maya Angelou’s poem “Human Family”:

“I note the obvious differences

between each sort and type,

but we are more alike, my friends,

than we are unalike.”

Kindly,

Tayler Shaw

Magazine Editor-in-Chief

Table of Contents

The art within the movement

By: Madeleine Kriech

Writer’s note: This article was originally written in June 2020 as a class assignment. The prompt: to mimic a New York Times style feature. This article was written in response to seeing many young activists use art as a way to help fund the Black Lives Matter movement, educate people on systemic racism in America and show how being Black in America made them feel.

It’s 11 a.m. on a Thursday morning in June, 2020. The voice on the other side of the phone isn’t as cheery as usual. When asked how he’s doing, there’s a long pause. There isn’t a good answer to that question.

“This is the time to put this out,” young activist Ashton Matthews says. “This is exactly the platform needed for this kind of art, to really get people thinking.”

In the fall of 2019, Matthews received a sweatshirt from his sister for his birthday. Written across the chest was the word “Unarmed” in large, white lettering. The 24-year-old knew that something special had to be done with this birthday gift. Remembering that his brother, Brenden, is a professional photographer, he got the idea to do a photoshoot that focuses on what it’s like to be a Black American. Unfortunately, the idea got away from Matthews as he and his brother had other things to focus on. However, the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd were the spark Matthews needed. He and his brother got to work. They used Matthews’ sweatshirt, red smoke bombs and a BB gun, sans orange tip, for their photo. Matthews posted the photos on his social media and his brother took prints to the protests in Denver. Strangers held up Matthews’ face high as they protested police brutality and racism in America.

“I’m not trying to be the face of a movement, but I’m trying to do my part,” said Ashton Matthews.

[layerslider id=”16″]

Art and protest have gone hand in hand for decades. Artists can be agents of change, as they are able to call attention to issues, sway opinions and direct reform. Looking back, art has been a part of some of the largest protests in American history, including posters from the anti-war movement in the mid 1900s to fashion statements from the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade and the modern day Womxn’s March. Music, paintings, fashion, posters, etc. have been a way for artists to express their beliefs and broadcast their movement to a larger audience.

And the Matthews brothers aren’t the only young artist/activist duo using their skills for change. Many young adults are using their art to speak out about Black Lives Matter and racism in America. Using their social media platforms, young artists are posting their work to raise awareness and even raise money for their cause. For 20-year-old hopeful fashion professional Juliette Jones, art is “something that always reinvents itself,” which is one reason why it’s so useful in protest.

Jones has been using her artistic ability to call attention to Black Lives Matter by starting a company called Masks for a Movement. For her company, Jones handmakes masks with different Black Lives Matter emblems on them, such as the Black Power fist and the Black Lives Matter logo. The aim of her new venture is to make money to donate to the Black Lives Matter Global Network, as 100% of her proceeds are being donated.

“If I were to take any of the profit, that would be part of the problem, especially because I’m white,” Jones says. “The way I market [my product] has to be very specific. Instead of marketing to benefit my business, it’s marketing to benefit the movement. I want to highlight Black-owned businesses.”

On her website under the resources tab, there are links to other organizations to donate to, such as The Bail Project and Campaign Zero, as well as a long list of educational materials about racism in America, including Don’t Touch My Hair by Emma Tabiri and The Color of Fear, directed by Lee Mun Wah.

“Black communities and Black designers have formed the fashion industry today,” Jones says when talking about prominent designers like Daymond John and Virgil Abloh. “Fashion is the Black Lives Matter movement. They are one and the same.”

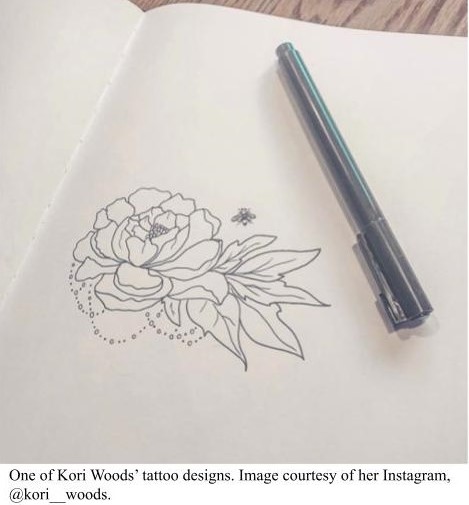

Usually busy with school, jobs and life, the coronavirus pandemic and its ensuing quarantine have been somewhat positive for young artists, affording them more time to dedicate to their art. Even before the pandemic hit, one of 20-year-old Kori Woods’ hobbies has been designing one to two tattoos a week. Now, she’s able to draw more tattoo designs without being “overwhelmed” with working on them in addition to school, work and the social strains that come with being a young adult. However, Woods believes if she did still have all that going on, her time spent designing tattoos would still be “worth it.”

Normally designing tattoos for fun, Woods now donates all her proceeds to Color of Change. She used to do her design work pro bono, but because of the Black Lives Matter movement, she decided to charge for her work and donate all her profits.

“The Black Lives Matter movement makes me feel really proud that people are fighting for change and that it’s outside of the Black community, who have been fighting for justice in this country for centuries,” Woods says. “It has helped me to recognize my privilege and pushed me to educate myself more on topics I’m not well versed in, and educate people around me in the topics that I am.”

“The Black Lives Matter movement makes me feel really proud that people are fighting for change and that it’s outside of the Black community, who have been fighting for justice in this country for centuries,” Woods says. “It has helped me to recognize my privilege and pushed me to educate myself more on topics I’m not well versed in, and educate people around me in the topics that I am.”

Although Woods and Jones have the best intentions by donating all of the profits from their art, other young artists believe this is the time for white artists to take a step back.

“People need to realize they need to support the Black people in their lives first before educating people on racial inequality,” says 20-year-old designer Dakota Nelson.

Nelson recently started selling her designs on RedBubble and is also donating her proceeds to Black Lives Matter organizations. She urges white artists to be aware of “white saviorism” and states that it isn’t “their movement to spearhead.” To help people understand why this is important, Nelson has started designing infographics on her art Instagram, @freewill.designs.dakota, in order to educate her followers about microaggressions, what it means to be an ally and other topics related to racism.

“I realized I needed to find a way to get my feelings out,” Nelson says. “I wouldn’t be doing justice to my own race if I didn’t speak up about this.”

Although newer to the world of graphic design, Nelson has made numerous Black Lives Matter related art pieces that are up for sale, including stickers, mugs and face masks. Some of her designs say “Black Lives Matter,” “Check your privilege,” “Mixed chick magic” and “Be Empowered.” Another one of her designs is a sticker saying “Black girl magic,” representing her desire to make artwork that “celebrates being Black.” She hopes to add some life into a movement that takes a toll on her soul.

Although newer to the world of graphic design, Nelson has made numerous Black Lives Matter related art pieces that are up for sale, including stickers, mugs and face masks. Some of her designs say “Black Lives Matter,” “Check your privilege,” “Mixed chick magic” and “Be Empowered.” Another one of her designs is a sticker saying “Black girl magic,” representing her desire to make artwork that “celebrates being Black.” She hopes to add some life into a movement that takes a toll on her soul.

“I’m so tired of living in this world where people in a group I belong to are being killed,” Nelson says. “[I’m] happy people are speaking up, but where were you before?”

Not all young, Black artists feel the same as Nelson. Matthews says, “White artists have a different platform. Being able to utilize that platform and create art that white people would understand regarding the Black experience—I feel like there’s potential there. It’s a fine line to walk.”

As for the future, Matthews says his “art will adapt to meet wherever the movement is,” but that his and other activist’s first goal is to “eradicate the need for the movement in the first place.”

Nelson also plans to continue with art and activism, looking to go to graduate school for media and advocacy. She believes the “world is finally really seeing the Black Lives Matter movement,” and that no one will be forgetting about it anytime soon.

The long timeline can wear young activists out, especially when Matthews states that “it’s much more exhausting just to be” as a Black man. Luckily Matthews, Jones, Woods, Nelson and other young artists will have their work to put their energy and feelings into.

“I’m a man just the same,” Matthews says. “I’m a good person. I don’t want to have to go through my entire life proving that to people just so I don’t get killed. Just because you know me and you know who I am doesn’t mean that somebody’s not going to see me in the same way they saw Ahmaud or Breonna.”

MLS: A model for change

By: Nic Tamayo

Writer’s Note: I got involved with the Multicultural Leadership Scholars program in the Fall of 2020. I’ve met plenty of amazing and diverse peers through the program. Even as programs like this one continue to evolve and spread across campus, they still remain largely unseen by the majority of the student body. This article was written in an attempt to “spread the word,” so to speak, to those who haven’t heard of programs like MLS. As CU continues to make progress in creating a diverse institution, being inclusive of all and being equitable to all, everyone should continue looking to the small programs, like MLS, that are fighting for change.

“When we are unable, or unwilling, to name whatever inequity it is we’re trying to address, it’s very hard to work towards that.”-Krishna Pattisapu, Ph.D. and Director of Diversity Recruitment and Retention in the School of Education

Diversity, equity and inclusivity should be the foundation on which major institutions are erected. Creating a space that is diverse and includes those of different races, religions, viewpoints, sexualities, gender identities and more in equal positions allows for a community to thrive.

While CU Boulder has made strides towards being a diverse, inclusive and equitable university in its 145 years of existence, it still hasn’t met the standards of many.

“Had I not had people back then, who were folks of color (faculty and staff), who pushed me and advocated for me, I wouldn’t have made it. So, I make it [a] goal of mine to be that person for our students because things haven’t changed.”-Johanna B. Maes, Ph.D., Director of Master’s in Higher Education and Senior Instructor for MLS

The CU Office of Diversity and Equity (ODE) was established in 1998, and it later was reformed into the current Office of Diversity, Equity and Community Engagement (ODECE) in 2007. Alongside the creation and development of this office, new programs were introduced on almost a yearly basis: CU LEAD CMCI Diverse Scholars in 2003, CU LEAD Education Diverse Scholars in 2004, CU LEAD Diverse Musicians Alliance in 2005, CU LEAD ENVD Designers Without Boundaries (DWB) in 2006 and so on.

These programs are great resources for diverse students, even if they aren’t enough.

The Multicultural Leadership Scholars Program, MLS, was established in 2017. It evolved from the former Chancellor’s Leadership Studies Program (CLSP) and the Ethnic Living and Learning Community Leadership Studies (ELLC) Programs and is housed by the CU School of Education.

“[In underrepresented communities], CU Boulder is [that] distant, ‘University on the Hill in Boulder,’ that serves mostly affluent white students from out-of-state.”-Derek LeFebre, Doctoral Student and Instructor for MLS

MLS is a melting pot of students, involving those of different ages, classes, races, sexualities and gender identities in an academic program. In classes, members work towards learning leadership skills and practices through a multicultural lens. In the accompanying “field practicums,” scholars work on projects aimed at creating change within local communities.

Johanna B. Maes, Ph.D. and Director of Master’s in Higher Education, has helped to build this program from the ground up. She was an instructor for the previously mentioned CLSP and ELLC programs and continues to work with MLS as a Senior Instructor.

“I’ve been associated with CU now as a student, as a staff and as a faculty going on almost 25 years,” Maes, CU Class of ‘92, says. Since she first began her relationship with CU in 1987, she says that “there hasn’t been a lot of change.”

MLS has long been a controversial program at CU. As a majority-white school, many students at CU don’t have personal experiences of oppression, discrimination or prejudice on account of race. This seemingly makes the study of others’ struggles less personal and, therefore, less important.

“There were many white students, who I used to teach, who didn’t like being taught about white privilege and didn’t like to be taught about racism,” said Maes. “We weren’t silenced, but we were told that we needed to tone it down[…] We faculty of color are treated very differently than white faculty.”

Similarly, Krishna Pattisapu, Ph.D. and director of diversity recruitment and retention in the School of Education, says that “[As] women of color, as femme people of color, there are so many stereotypes and unfair expectations [that] precede us before we ever step foot into a role.” Pattisapu is an instructor for MLS. As an Indian-American nonbinary person, Pattisapu has been no stranger to the adverse effects caused by a lack of diversity, inclusivity and equity.

Intersectionality is a widely talked about concept first coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in her essay “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Anti-discrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” Essentially, it’s a theory that considers how differentiating identities (race, class, age, etc.) may affect people. Intersectionality is a staple in the curriculum of MLS as it helps students understand situations through a multicultural and multidimensional lens.

Pattisapu describes intersectionality as something she dealt with internally before it became a widely accepted notion in mainstream spaces.

“I have always embodied it because that’s who I am,” she says. “I have all of these intersecting pieces of who I am that inform how I approach my job and who I seek [to help].”

Derek LeFebre, a doctoral student and instructor, currently leads MLS’s “field practicum” program. He says that CU, in his experience as a first generation Latinx student, has more inclusivity and communities for minorities than previous institutions that he’s attended.

“As an instructor, I get to help create a space for others who are very similar to me in those two particular areas,” says Derek, referring to being first generation and a student of color. “I get to create a space […] where we as students can grapple with our identities [at] an institution that isn’t necessarily created for us.”

He credits MLS and the School of Education for allowing him to help create a community for undergraduate students that provides security and safety for underrepresented students at CU.

MLS is a small scale experiment that utilizes the principles of diversity, equity and inclusivity in its teachings. Through this, the program has helped to aid budding multicultural leaders. This program paints a hopeful picture for CU at large.

“I’ve seen students who have been tremendous social change agents after they’ve finished our program and graduated from CU,” says Maes. “They have our foundation that we taught them as a launching pad to the work that they do.”

“I hope that CU finds a way to make diversity, equity and inclusion not a job of those who are from marginalized backgrounds, but a job that is encompassed and explored and embraced by white populations.”-Johanna B. Maes

“It’s more than just throwing money at students to attend, [it’s] about convincing students that this university is as much yours as it is anyone else’s.”-Krishna Pattisapu

“I would like to see CU become more accessible to your local Coloradan, who is maybe from a low-income family and, right now, I don’t believe that CU is accessible.”-Derek LeFebre

MLS is open to students of all majors who want to earn a minor in Leadership Studies (including sophomores and juniors). Applications from BIPOC students, first-generation students and LGBTQ+ students are strongly encouraged. Those interested can apply by April 1, 2021. Applications are reviewed on a rolling basis.

From South Sudanese refugee to Colorado teacher

By: Alisa Meraz-Fishbein

Correction: On Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021 this article was updated to reflect that Nyibol Bior attended CU Denver (not DU) and works as a teacher in Dolores, Colorado (not Longmont, Colorado). On Sunday, Feb. 7, 2021, the article was updated to reflect that Bior attended Texas A&M International University (not Texas A&M University).

Nyibol Bior was a year old when Sudan entered its second civil war. At five, she was torn from her Sudanese home and sent to an Ethiopian refugee camp. She covered over a thousand miles on foot at age eight, seeking refuge and stability from the war. Thirty-eight years later, Bior now serves as a teacher in Colorado, inspiring children and giving them the strength to persevere through their struggles.

The second Sudanese civil war erupted in 1983 due to unrest between the north and the south regions. Rebels from South Sudan created the Sudan People’s Liberation Party (SPLA) to fight against the Sudanese government, primarily composed of Northern Sudanese civilians. These northern leaders wanted to impose Islamic law, much to the southern population’s dissent.

Nyibol Bior was born in 1982 near the border of what is now Sudan and South Sudan. Once the war began in 1983, Bior’s father joined the South Sudanese rebels fighting those in the north. Due to political unrest, her family was forced to flee. However, one-year-old Bior and her three-year-old sister were too young to travel. As a result, they went to live with their grandmother, who was further from the conflict, while Bior’s mother and older brother went to a refugee camp in Ethiopia.

In 1987, Bior and her sister were old enough to join their mother and brother in the Ethiopian refugee camp. Although she was reunited with the majority of her family, the transition took a tremendous toll on her.

Bior says that her grandmother had become “like my mother, and going to be taken to the refugee camp in Ethiopia was devastating.”

During the year 1990, Bior and her family were continually displaced. Conflict began to overwhelm Ethiopia, resulting in their return to Sudan. However, due to the ongoing war in Sudan, the family was forced to relocate once again to a refugee camp in Kenya. Bior, only eight at the time, walked over 1,000 miles that year.

Bior recalls the journey from Sudan to Kenya vividly. She was with her mother, older brother and sister, and two new siblings that her mother had given birth to in Ethiopia. The younger children were carried, but Bior and her older siblings had to walk.

“I don’t know how I made it,” Bior says. “I wanted to be left in the wilderness to die. I felt death before I knew what it was. It wasn’t an easy journey, and it left a lot of scars.”

Bior’s father joined the family in Kenya. Once he arrived, he was wrongly accused of defecting from the rebel group SPLA. He was taken from his family, tortured and put in jail. The United Nations investigated and found out that many men, including Bior’s father, were wrongly arrested. As a result, they were granted asylum.

The family’s end goal was to receive asylum and move to the United States. Navigating the bureaucratic roadblocks took time; the family was taken to Nairobi, Kenya and given an apartment to live in until the vetting process was completed. The vetting process consisted of interviews and health exams, and it took four years to complete. During that time, Bior’s family resided in Nairobi, where the children were able to attend school.

Bior and her family moved to Dallas, Texas, in 1995. Bior, age 13, enrolled in the seventh grade at a local school and was put in the “English as a Second Language” program. At the time, Bior was fluent in the Dinka language, her native tongue, and Swahili, which she picked up in Kenya. The other children in her ESL class primarily spoke Spanish and Vietnamese and were able to talk to each other in these languages. However, no one knew Dinka or Swahili. As a result, she was forced to rapidly pick up English to make friends and communicate with her peers.

Bior’s cultural and linguistic barriers posed an immense challenge to her. She worked very hard in the classroom but was lonely because she didn’t have any initial friends.

“At times, I would go home crying every day. I was picked on a lot because I was from Africa and [have] a very dark skin complexion,” recalls Bior.

When she did make friends, it was hard to keep them because her family continually moved throughout Dallas, and she switched schools frequently.

Where she did find success, though, was through her academics, as her hard work and determination in the classroom paid off. She attended Texas A&M International University and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in physical education in 2006. Eight years later, she went back to school at the University of Colorado Denver and received a master’s degree in linguistically diverse education. Today, she works as a high school special education teacher in Dolores, Colorado.

Bior enjoys her job, though she continues to face adversity and often questions her place in the United States. Although she has spoken English for most of her life, she still feels like people don’t understand her accent.

“Sometimes, people have to ask me questions over and over again, and it’s extremely defeating because I know that doesn’t happen to someone who’s a native speaker of English,” Bior says.

She often feels behind her peers because English is her third language, and she missed a lot of education as a child.

“Every time I am unable to answer questions correctly about my field, I feel the other person might think I am unqualified to do my work,” says Bior. “It’s upsetting because I spent so much time studying to become a teacher.”

Nonetheless, she persists. Her fighting spirit has never left her, and she continues to educate children and give them courage to overcome their own challenges.

“My hard work has led me to be where I am right now, allowing me to pursue my passion of motivating others.”

From a wooden desk to the real world: Inequalities in the classroom

By: Abby Schirmacher

Click here to listen to an audio version of the story, narrated by Abby:

Diversity. Everyone interprets the term differently, as there are a variety of areas in society lacking inclusivity. Often, minority groups in social, political and economic circumstances are defined by the notion that differences are frowned upon.

We learn this idea at a young age. Time in the classroom is meant to be spent learning about history, math, outer space and the ABC’s. However, we also, often subconsciously, learn to distance ourselves from those of the opposite gender, those with different skin tones or peers with less money than our parents. We teach our children that when you look at another person, your face in the mirror should be staring back at you. We preach diversity, while the classroom doesn’t.

Only 19 years ago, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school (CMS) district in Charlotte, North Carolina ran a segregated bussing system. Strategically implemented to integrate racial groups into different schools, students were bussed outside of their local communities and attended schools based on racial composition. Matthew Delmont, author of Why Bussing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation, describes how this system failed, explaining that bussing “failed to more fully desegregate public schools because school officials, politicians, courts and the news media valued the desires of parents more than the rights of black students.” The bussing system, which eventually ended at CMS in 2002, created ripple effects that impacted students of color for years to come, and it represents a reality that’s surfaced in mainstream media this year: racism in the U.S. is alive and well.

Associate professor Stephen Billings at the Leeds School of Business at CU Boulder observed the aftermath of race-based bussing at CMS. Following a court order to disband this system, students faced challenges academically and socially. Through in-depth research on test scores, criminal activity and educational value and success, Billings and his fellow researchers came to a conclusion: resegregation of CMS schools prompted an increase in racial inequality.

“Overnight, they went from this pretty even mix of minority and non-minority students to where we had schools that had like 90% minority and other schools that had 90% non-minority or white students,” Billings says. “Mostly, it tended to hurt, or in essence increase, that gap between minority and non-minority students— meaning that it tended to hurt the minority students the most.”

Inequity in the classroom is present in other ways. Often, women hesitate to enter science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields due to ostracization from their male counterparts. According to a study conducted by the Society of Women Engineers, women make up about 21% of those pursuing bachelor’s degrees in engineering and computer science. The long standing legend that women aren’t cut out for these positions appears in underlying ways today in academia and the workplace.

Undergraduate student in applied mathematics Kaitlin Coleman feels her fair share of the repercussions of being a woman in classes dominated by men. In some circumstances, her ideas are shut down without good reason, and in others she notices the lacking representation of female professors in her field.

Though this isn’t an easy feat, many STEM women continue to pursue their passions and hope to make a difference in their fields. A part of their success involves constant communication with their peers.

“Something that I think is really important is establishing connections with people first so that they can understand where you’re coming from, and being able to work closely with someone where they can understand how your brain works,” says Coleman.

The classroom environment is also a major contributor to individual political beliefs and the overall political atmosphere of society. In a study alongside several other economists, Billings found a correlation between white students exposed to minority groups at a young age and their future political affiliations.

“If you’re a white kid and exposed to more diverse students, it makes you less likely to be a Republican in your late twenties,” he explains. “It’s not clear why […] but it is consistent with this idea that they’re going to be more likely to favor policies that deal more with promoting equity.”

“There’s less fear of unknown groups, things like immigration, [so] they will be more inclusive with those types of groups,” Billings continues.

Billings’ study, which was published in The Washington Post, highlights fundamental ideas presented to students at a young age. On the surface, it is clear that different regions in the country are demographically associated with racial groups. Billings’ findings show that political affiliation may largely contribute to our surroundings at a young age, where students exposed to those different from themselves and their familial circumstances enter society with more awareness towards minority groups and social issues.

Coleman addresses this idea regarding her knowledge of issues surrounding diversity and inclusion. As a member of the LGBTQ+ community herself, “[that] was a doorway that allowed me to learn about other minorities and other ways […] that different groups of people experience oppression and inequality,” she says.

Similarly to education, inequalities appear in the workplace. Nowadays, education on diversity and inclusion in the workplace defines employee relations, public relations and more. Successful businesses and corporations are being held accountable by a societal push for change.

Emily Shepardson is spending her mid-twenties working on the frontlines for a large corporation. After leaving academia, she realized that “discourse is amazing and important, and so, so influential. It’s also just another small piece of the puzzle because […] I don’t have a lot of extra time to read and listen to podcasts and stuff.”

Attending schools within a certain district for one’s entire academic career or remaining in an exclusive bubble can affect a person’s future understanding of the world and of others. Diversity of experience allows individuals to develop empathy for those on different paths of life.

“People get lost in the idea of a minority group and that discourse can only go so far,” Shepardson says. “I miss having the discourse, but learning from life experience, listening to other people’s personal experience and making the time when I have it [is valuable].”

This past year, inequality in this country surfaced in the media and national politics. In response to injustices faced by minority groups daily, many U.S. citizens are demanding action through implementing new policies, transforming governmental institutions and encouraging increased awareness of social inequalities. At the micro level, learning to be more accepting of those different from us is vital in enacting change.

One method of change is diversifying neighborhoods, as neighborhood composition affects schools, which leads to differing educational curriculums that influence children’s future opportunities. However, this will take intentional action by others, as currently “People are more comfortable living with people who look more like them,” according to Billings.

Billings offers that the attempts to address this problem through one-dimensional diversity and inclusion policies today “are a little misleading and [don’t] really help us… It’s too much checking the box and not really kind of trying to get diverse perspectives in a meaningful way.”

The issues plaguing this country today are few and far between. From an institutional standpoint, issues of discimination in education will continue to flourish without action, such as in the instance with race-based bussing. However, individuals serving as bystanders and allies could fundamentally change the discriminatory ideologies deeply rooted in U.S. history.

“As white and privileged people, we need to start standing up and calling it out as we see it because I mean, we’re the ones who did the damage in the first place and that’s the first step to undoing it too,” says Coleman. “Especially in our bubbles, you know? Being able to stand up to your friends who are making rude comments or degrading comments, or even if they have an opinion on something that you think is a little off. I think that’s where it needs to start.”

As we continue to grapple with our understandings of diversity and how to create a more equitable and inclusive society, it can seem like an impossible issue to tackle. However, individual and unified action can serve as a method for creating proactive change, no matter how small it may seem. So the next time you’re in class and notice underlying inequity, ask yourself: what can I do to change?

Appreciating rap and hip-hop has been a learning experience for my white father and I

By: Nathan Bowersox

Click here to listen to Nathan and his father narrate their story:

Background music: “Rogue” by Yung Kartz

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Writer’s Note: Rap and hip-hop are listened to by a wide variety of people from all walks of life, including those who are white. The concern that arises from white people listening to rap music is the appropriation of hip-hop culture. Cultural appropriation is defined in the Cambridge English Dictionary as, “the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you respect this culture.” Cultural appreciation, on the other hand, is the act of acknowledgement and respect for a culture, using it as an avenue to learn from the experience. Rap music can both be appropriated and appreciated by white people. The goal is to ensure that white people are aware of their appropriating habits and transform them to appreciate the music, especially for avid listeners of rap music like myself and my dad.

I am a 20 year-old straight, white male studying at The University of Colorado Boulder. My love for rap music came from my dad, who introduced me to the genre at a fairly young age. He is a 45 year-old straight, white male who runs a small, successful blue-collar business in Douglas County, Colorado. I was raised by my dad in the affluent town of Castle Rock, which according to the most recent census is 92% white. Rap has become a learning experience for my dad and I due to our positionalities and the cultural bubble that we grew up in. Through our narratives, we want to showcase how the only choice is to appreciate hip-hop culture, especially by reflecting on mistakes we have made in the past. These narratives also provide context into our introduction to rap music, stories of us appreciating rap music and why we have grown so fond of the genre. This autoethnography showcases the journey from one generation to another, through the lens of rap music and hip-hop culture.

Our stories and analysis of listening to hip-hop and rap

Hip-hop culture and rap music can be a learning experience, especially for people of privilege, although many may not treat it as such. People like myself and my dad, who grew up in primarily white neighborhoods and white schools, get a very limited chance to learn about Black culture. Hip-hop and rap music can be an opportunity, or introduction, to learn about aspects of Black culture. My dad explains his first experience with rap music and why he was drawn to it:

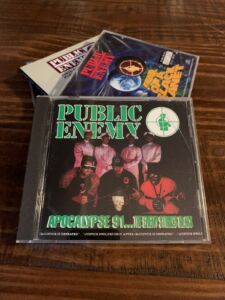

“I first listened to rap music when I was about 12 years old in 1987. I lived in a lower income, working-class, predominately white suburb and listened to new wave alternative and punk music prior to that. My social group were punks and skate boarders, and we all took to rap music because it had a very anti-establishment message which was parallel to our punk music. We listened to socially conscious rap like Public Enemy, KRS-One and Eric B. & Rakim, lyricists who taught us about African American struggles that we were unfamiliar with. We would skate to rap… the rhythms and the beats were way more infectious than some of the Alt “white” bands we listened to prior. It was great to listen to while skating half-pipe.”

Hip-hop entered its “golden age” roughly around 1987, with new artists and modes of expression being formed through the medium of rap. My dad touched on the rebellious nature of rap music, it being an avenue for him and his youth to express themselves. He also explained how it was a learning experience for him. This fascination for hip-hop stems from its ability to teach people about the culture through its counter-hegemonic messaging. Many white people have a lack of exposure to other cultures, which hinders our ability to have real-life dialogue and gain knowledge about the experiences of others. Real-world interaction and engagement is irreplaceable to learn about struggles, but listening from a first-person point of view through rap music is also incredibly insightful. Learning about others’ struggles is an important aspect when reflecting on your own positionality and privilege.

My dad provided some names of rappers from the era who were able to inform him about Black struggles. “Paid in Full” by Eric B. and Rakim released in 1986. It tells a story from Rakim’s first-person view about how money—and therefore capitalism—can trap Black people. One of the most notable songs from this time period that exemplified struggles of the Black community, sparking a nation-wide rally, was “Fight The Power” by Public Enemy. In the summer of 1989, it became a catalyst for free speech and highlighted the struggles that the band members had faced in their own lives. In an 2014 interview for Rolling Stone Magazine, Hank Shocklee, founding member of the rap group, stated:

“We lived in the suburbs and were sandwiched by nothing but white communities. It was like we were the leftovers: We got what the white communities didn’t want to have, we got their spillovers. So we always had to kind of fight this adversity. We wanted to just make something that was going to say, “I’m mad as hell, I’m not gonna take it anymore – I’m going to fight the system.”

“Fight The Power” is known as one of the greatest rap songs of all time for its ability to acknowledge the issues and use its lyrics to empower a rebellion for the greater good. This is just one of the examples from the time though that both informed and fought for change. A few years later, KRS-One released their hit single “Sound of da Police,” which was able to showcase the power difference between police officers and those in the Black community. It was an era of rap music filled with incredible moments of challenging oppression.

My dad listened to all of these songs and became attuned to the issues that were happening in Black communities. I asked him if he was appreciating or appropriating the culture by listening to rap music. He acknowledges his moments of both appropriation and appreciation throughout his life:

“Both, especially when I was a kid and a little less informed. I remember rap music elicited me to write a history paper on Huey P. Newton, Co-founder of the Black Panther Party, when I was in high school: appreciation. However, I also used to walk around with a Georgetown Starter jacket and trying to “look hip-hop?” without a real understanding that I was taking from a culture, or even a heavily African American university program. Sadly, I had the privilege to immediately incorporate all of the “coolness” of rap culture without any of the danger or sacrifice. As I have gotten older, my appreciation is through the roof, where my appropriation has hopefully been filtered a little more carefully.”

I believe that we all have had times of cultural appropriation and appreciation, like my dad has explained. Kathryn Sorrells, author of “Intercultural Communication: Globalization and Social Justice,” provides some background on the appropriation of hip-hop culture, writing: “The meaning of appropriation varies along a continuum from the idea of “borrowing” to “mishandling” to “stealing” and raises questions about authenticity, ownership, and relations of power.” Certainly, my dad wearing the Georgetown Starter jacket is a form of appropriation. I believe that my dad has recognized his privilege and that moment of appropriation, and he is currently very appreciative of rap music. The goal is to make sure that we are all working towards appreciation. It’s part of the reason why my dad first introduced me to rap music:

“It’s all about the music. Everything about hip-hop gives us a lens to learn about people in the African American community that we wouldn’t otherwise learn or understand given where we/you were raised. It’s not just the spoken lesson we get, but the way they package it and present it, beats, flow, theatrics of ego… everything. It’s a learning experience that is packaged with perfect artistry.”

My dad used rap music as a way to teach me about things that I otherwise wouldn’t have had the opportunity to learn. My positionality made it difficult for me to understand things that were happening outside of my cultural bubble. Rap music provided me with a better teacher of these issues than my dad could ever be and I certainly wasn’t learning any of this in school. He showed me the same songs from when he was younger, as well as many more. While we drove in the car, he would play the music and tell me to pay attention to the lyrics. After a song would finish, he would pause the music and help my young mind unpack the history behind the lyrics. He would explain what was happening during the time of recording and what the lyrics were meant to convey. My curiosity was piqued and I would ask more questions in order to get full understanding. These conversations would happen often and was a great way for me to learn about the oppression and struggle of many Black communities.

As I got older, I became more interested in rap music and hip-hop culture. I started to branch out from the rap music that my dad had introduced me to and discover more modern artists who would tell similar stories as their predecessors. Logic, J. Cole, Kendrick Lamar, Kid Cudi, Kanye West, Childish Gambino and many more filled my ears on the daily. I loved the technological nuances of the modern era of rap, but still gravitated towards the music that was driven by honest lyrics that were socially conscious. Logic’s first studio album, “Under Pressure,” marked the first time that I had shared something entirely new with my dad: We were riding around in my dad’s jeep in the winter of 2014. I asked my dad if I could have the aux jack, letting him know that I had an album for us to listen to. He smiled while handing me the cord. I could sense his anticipation. Specifically, the song “Gang Related” taught us about Logic’s dangerous and violent childhood; the struggles of residing in his broken home in Gaithersburg, Maryland. It was such a stark contrast to how my dad and I grew up and really allowed us to reflect on our own privilege. Another moment that struck us while we were listening to the album was when my dad and I listened to “Nikki.” This song is about the struggle of addiction, which is something that he knew personally and it moved him. This is why I love rap music. It has this ability to open your eyes unlike any other genre.

Dad wasn’t stuck listening to the same music that he grew up listening to as a kid. He had this incredible ability to find new hip-hop that I didn’t. He continued to watch rap and hip-hop evolve into the modern era. My dad and I can both appreciate rap and hip-hop from the old and new. I recall a moment where my dad sat me down and made me listen to Jidenna’s debut album, “The Chief.” It was a warm summer day up at our cabin near Deckers, Colorado. I heard my dad call me into our living room. He said, “Sit down.” I promptly sat down on our couch wondering if I was in trouble, thinking about all of the mischievous things I had done in recent memory. Dad grabbed his phone and plugged it into our sound system. He looked at me and said, “Just listen.” I smiled, knowing that class was in session. It had been a while since we had listened to music like this together. A year prior, I got my driver’s license, which meant that we didn’t spend as much time together in the car sharing all of the music that we were finding and learning from. He joined me on the couch and let the music fill the room. We both listened attentively to the entire duration of the album, 57 minutes and 30 seconds to be exact. The album was something so different than I had ever heard.

Jidenna is an American-Nigerian rapper and some songs on the album gave insight to his multicultural upbringing through thoughtful and well crafted lyrics. Other songs acknowledged the pressing issue of current-day inequalities and police violence. The album is a journey that blends many different hip-hop elements and had an African flair that made it extremely unique. This is one of the most clear moments of how my dad and I have bonded over music that I can remember. To this day, I still listen to this album because I don’t want to forget the moment of both bonding and instruction. I find that I learn new things every time I listen. Rap has given me and my dad an overwhelming curiosity about race and cultural relations in the United States. I am always eager to learn and listen to rap music, old and new. From learning and listening, we get this beautiful opportunity to engage in thoughtful dialogue together, and the first step is awareness.

Like my dad, I want to be able to pass on this love and appreciation for rap music and hip-hop culture to the next generation. Through their own discoveries I am excited for the moment where they can show me what they are learning. It is incredibly important to understand what happens within other cultures, especially because of its capability to open reflection of your own positionality and privilege. Rap has given my dad and I that ability to not only learn, but actually engage in intercultural communication together. I would certainly be lost without all of the experiences that rap has given me, and I am incredibly grateful for my dad who showed me the way.

Learning how to become an ally: A self-reflection as a white woman on the racial injustices in our country

By: Claire Purnell

I have always known that I’m a white woman with blonde hair and blue eyes– but I didn’t know until this past summer that I also have white privilege. I have never faced discrimination in the ways that people of color have. And for the longest time, I did not even understand how unequal my life was in comparison to a Black woman my age, simply due to a difference in skin pigmentation.

I grew up in a small, upper class town in Louisville, Kentucky. I went to an elementary school with about 50 students per grade. Then, I attended a small private high school with about 100 students in each grade. In elementary school, I saw almost no racial, ethnic or cultural diversity. In high school I saw a tiny bit more, but not nearly enough. After two years of high school, I moved to online school due to the demands of my sport of figure skating, limiting my world.

Throughout my youth and naivety to the world around me, I never thought or even considered that I exist in a racist society and contribute to the inequities in our country. I did not consider the fact that I have a similar background and appearance to most of my friends and that was an issue. I hate admitting this. It pains me that ideologies I have been taught from school and society have harmed communities of people for a long time. But admitting these beliefs and realizing why they are wrong is a crucial first step in our journeys towards equality for everyone and being the best ally possible.

Last spring, I remember seeing #IRunWithMaud all over social media and watching the video of an innocent Black man, Ahmaud Arbery, being murdered while out for a jog. It really stuck in my mind for a while, but it was not until the death of George Floyd and the cry for help that occurred from the Black community made me reconsider my privilege and become educated. After the Black Lives Matter protests, I was confused because I felt like the world was blowing up all of a sudden even though it was just me finally noticing the severity of the inequality and discrimination that still exists in our country. I think being inside constantly on our phones due to the pandemic finally made us listen to the melanated voices that have been yelling for so long. It made many of us change how we think and act, and we need to continue this work after the pandemic ends.

Through engaging in readings, podcasts, documentaries and videos, I learned a lot. I learned how racism is not just using slurs or derogatory terms or discriminating against people based on color; it is also limiting yourself in circles of privilege, as my circle was predominately white, and never questioning it. I learned that change won’t come from the top-down; it will come from starting the conversation in the car with your white friend if they sing the N-word along with a song. I learned that I will never understand the pain or frustration of BIPOC communities, but I understand their right to be. Thus, I want to be an ally and help in spaces I am allowed into.

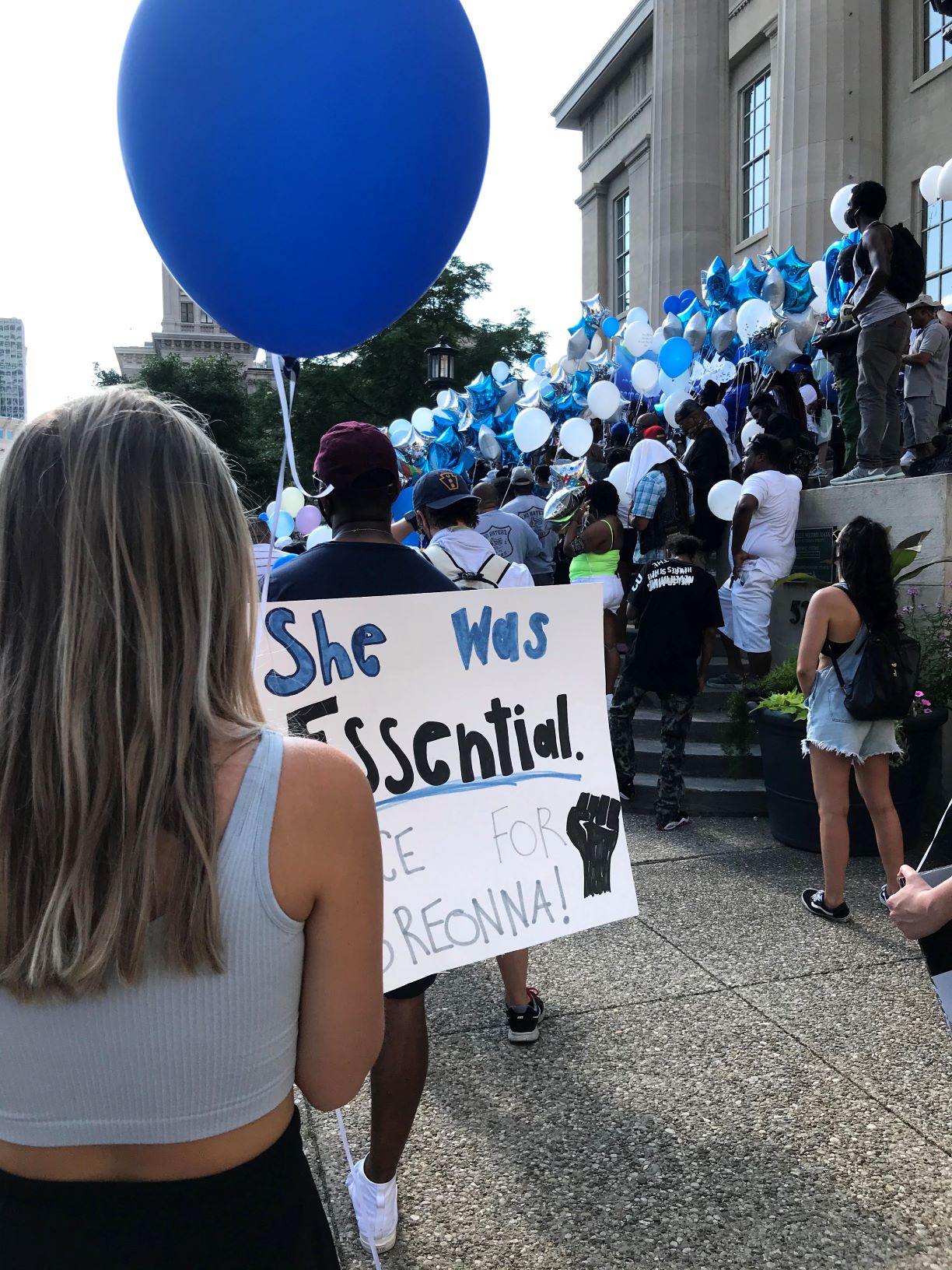

I was in Louisville when racial inequities were exposed and protested in 2020. Louisville has always been my home since the day I was born. It was also Breonna Taylor’s home and where she was murdered by Louisville PD; yet, another instance of police brutality. On June 5, her birthday, there was a vigil for Taylor in downtown Louisville. I spent my morning making a poster for her that said, “SHE WAS ESSENTIAL.” I bought blue and white helium balloons which were requested by the people running her vigil.

Neither of my mom nor I had been around a group of people since March, and it felt really strange, but the other feelings present at this vigil were much more powerful. There was yelling, singing, crying and chanting. There was sweat, tears, anger, hope, sadness and a longing for a necessary change. I stood to the side of the people speaking – Taylor’s family, local activists and Reverend Jesse Jackson. I went to these events because they were protests, but more educational ones. I wanted to be involved in the fight but also, do what I could do to understand and to help by listening and standing in support.

The following week, I attended a walking prayer vigil again in downtown Louisville. This one was more educational and was aimed more at educating allies. At one point, one of the speakers shared a quote from Malcolm X that stood out to me more than anything else: “You can help us, but you can’t lead us and I appreciate your willingness to step up, because in order for any change to be made, we’re going to have to do this together.”

Too many people showed up for us to be able to safely and distantly do the walk, but we listened to three hours worth of different perspectives, stories and ideas of ways we can create a more just society. I left inspired to keep learning and changing. I found more resources and wrote my first piece on the movement to share on my blog. A month before, I would have been too afraid to speak on this topic because it was unfamiliar. Now, I am able to engage and grow, accepting criticism and asking the right questions to become a better ally. In order for change to be made, we all have to start stepping up. I stopped being too afraid to say the wrong thing. I realized that being silent only makes things worse, and I decided I would just try to speak out.

I began to have conversations about race, discrimination and the importance of anti-racism with various people in my life– including in my sorority, Alpha Phi at the University of Colorado Boulder. I will not pretend I am changing the world or that I even understand half of the inequity Black people face every single day, but I will continue doing what I can to fight for equality in our country. If I could share one main idea I took away from all of my reading, listening and watching it would be this: Your actions matter.

For those who come from a similar background as myself, starting small is what makes change happen. Have the hard conversations at your dinner table. Call your friends out (in a productive way) when they say something you know is wrong. Share resources, keep donating and keep learning. If I do anything with this piece, it is to tell you that every single person can help make this country more equitable if you just commit to trying.

Listed below are some of the useful resources I’ve discovered:

Resources

- Almost 30: episode –> “Revolution Now”

- ILYSM podcast : episode –> “A conversation with Dom Roberts”

- GalsontheGoPodcast : episode –> “A conversation about race and privilege with Chloe Coriolan”

- 1619 NYT all episodes

- Let it Out: episode –> 301

- NPR Code Switch

- Healthier Together: Episode 47 with Ivirlei Brookes

- @karl_shakur on Instagram -> What should I do?

- Act dot tv Systemic Racism Explained

- @gisele_milan on Instagram -> Dear white people, so you want to be an ally?

- The Daily Show

- A speech by Zianna Oliphant

- @ivirlei Instagram -> White Women Who Truly Want to Help: Here’s How

- Julia Lucero-Orebaugh on Instagram: “As the conversations of racial injustice continue, it is crucial that we all prioritize learning in order to create both internal and…”

- so you want to talk about… on Instagram: “White privilege NEEDS to be discussed. Widely. It also needs to be recognized. Especially during the middle of a pandemic when so many are…”

- Maria Sosa, MS, MFT, Therapist on Instagram: “Anti-racism work is human growth work. . We are a growth oriented culture…”do more, have more, be more”…with everything…BUT being a…”

- Nina on Instagram: “friends! checkout these covert forms of white supremacy, and please share this with your white friends who say they are not racists; it’s…”

- 13th Documentary

- The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas (book and movie)

- Me and White Supremacy by Layla Saad

- White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo

Magazine Contributors

Tayler Shaw is a senior majoring in journalism and Spanish for the professions and minoring in anthropology and leadership studies. She is from Littleton, Colorado. Her interests include explanatory and solutions journalism on topics ranging from education, culture and community-based issues.

Claire Purnell is a sophomore journalism major at CU Boulder. She is from Louisville, Kentucky. She ended her ice dancing career in 2019 to follow her dreams of being a writer and to experience a normal college life. Claire is now a spin instructor, Diversity co-chair of her sorority (Alpha Phi) and she loves all things health, happiness and fitness.

Nic Tamayo is a freshman studying journalism at CU. Originally from Colorado Springs, he’s an avid baker, a lover of literature and a (former) barista.

Abby Schirmacher is a junior majoring in journalism and minoring in business and sociology. She is from Erie, Colorado. Abby enjoys spending time with her family and friends, binge watching her favorite Netflix shows and studying at local coffee shops. She also loves to read, write and hike in her free time.

Madeleine is a senior from Parker, Colorado, studying political science and evolutionary biology. Besides writing, she likes crafting, watching movies, listening to music and trying new foods. Her dream is to live in a big city and work as a journalist.

Alisa is a junior majoring in journalism and minoring in creative writing. She is from Albuquerque, New Mexico. Alisa is a member of the CU track and cross-country team and loves exploring Boulder trails with her teammates. In her free time, she enjoys spending time with family and friends, making art and, of course, binge-watching Netflix.

Nathan Bowersox is a junior pursuing a major in advertising, a minor in business and a writing certificate. He is originally from Castle Rock, Colorado and enjoys playing golf, volleyball and collecting sneakers in his free time. He is also the marketing manager at The Bold.